by Errol Black

Canada’s Employment Insurance (EI) System has been much in the news in recent weeks. The main issues are long delays in processing EI claims resulting from the Harper government’s attempts to automate and depersonalize the way claims are processed, and increases in EI premiums effective January 1.

A December 17 report in The Globe and Mail by Gloria Galloway, titled “EI cheque delays fuel pre-Christmas client outbursts,” tells the story of how the service provided by Service Canada workers has been undermined because of the elimination of hundreds of jobs in 2011: “[Service Canada] workers say the federal government’s [elimination of processing agents] is forcing some jobless Canadians to wait months for their first benefit cheques. And the shrinking staffing levels at Service Canada call centres have created phone lines so overloaded just one in three callers actually reaches an agent. That means more people are turning up at the centres to find out when they will get paid.” Galloway notes that Diane Finley, Minister of Human Resources and Skills Development, claims the elimination of jobs is part of an effort to move from a “paper system to one that is automated.” Service Canada employees who are providing the service suggest this is not true; the system has been automated for four years, now they’re getting major cuts to jobs.

In an interview with Bruce Owen of the Winnipeg Free Press (“Welfare fills gap as jobless wait for EI,” December 30, 2011), Neil Cohen, executive director of Winnipeg’s Community Unemployed Help Centre, confirmed that it is the Services Canada employees who are telling the truth about what’s causing the EI claims crisis, and not Diane Finley. Cohen also explained that one of the consequences of the long delays in getting their claims processed is that many unemployed workers are forced to turn to Manitoba’s social assistance program to tide them over until they get their EI cheques. When Cohen was asked if there was a solution to the problem he said there was: “They’re laying off staff. They’re closing call centres. They’re closing claims-processing centres. They’ve prohibited staff from working overtime, so yes there’s a fix…”

The comments made by Service Canada workers and Neil Cohen were echoed by Pat Martin in a story in the Winnipeg Free Press on December 31, 2011 (Bruce Owen “Claim-filing logjam has MP furious with feds“): “Our office has been inundated with complaints from people who simply can’t access [EI]. You can’t consolidate and cut back Service Canada and not have a corresponding [negative] impact on service.”

This is indeed a sad story, especially for the tens of thousands of workers who are dependent on EI to tide them over the rough patches in their employment experiences. To add insult to injury, on January 1 the Harper government raised the price to employees for these deteriorating services to 1.83 per cent per hundred dollars of insurable earnings from 1.78 per cent.

It seem clear that the Harper government doesn’t give a damn for the misery and grief its policies and practices have caused unemployed workers. Nor apparently do most provincial and municipal governments that also have unemployed citizens in their jurisdictions. The City of Brandon did raise the issue of cuts to staff and services in a letter to Ottawa in June 2010. Ottawa dismissed the concerns as unfounded and said that service to unemployed workers would be improved.

What is to be done?

A place we might start is to organize unemployed workers, trade union members and others to make formal presentations to MPs, MLAs and Municipal Councillors and informal representations through information picketing. We must demand immediate improvements in service, and also the adoption of reforms to the EI system as proposed by the CLC and affiliated bodies. This would not only be a timely response to the plight of the unemployed, but it would also be a useful way to prepare ourselves for the intensifying struggles yet to come as the Harper government moves forward with austerity measures that will undoubtedly see a further downsizing of government in addition to further changes to the tax system that will disproportionately benefit the rich in Canada.

Errol Black is a member of the CCPA-MB board.

by Errol Black and Jim Silver

Each of us read Steve Brouwer’s Revolutionary Doctors (MR Press, 2011) the same week the media reported average gross fee-for-service earnings of Manitoba doctors at $298,119. The media also reported, again, that many Canadians do not have access to a family doctor; that some specialists are in short supply; and that health conditions in many Aboriginal communities are appalling.

While we are fervent supporters of Canada’s Medicare system, we think there is much to be learned about health care from Brouwer’s book.

First, Cuba produces large numbers of high quality health care providers, including doctors—more doctors per capita than any country in the world. This is a tribute to the quality and cost—free tuition—of their entire education system. The benefits to the Cuban people are reflected in two key health indicators: average life expectancy in Cuba at 77.7 years, while behind Canada at 81.4 years, is on a par with the U.S. and higher than most countries in the Americas; the infant mortality rate (number of deaths of children under one year per 1000 live births) at 4.90 is the same as Canada at 4.92, and less than the U.S. at 6.06.

Moreover, at Cuba’s Latin American School of Medicine, established in 1998 as part of the Cuban vision of a “caring socialism” rooted in international solidarity, large numbers of international students are studying to be doctors. This includes 23 Americans who enrolled because they are unwilling to take on the $150,000–200,000 in debt to pay for a U.S. medical degree, and are attracted by the obligation, in return for free tuition, to return home to practice medicine in poor communities.

Second, large numbers of Cuban medical personnel are sent around the world in response to natural disasters. Cuba’s medical team was particularly important in responding to Haiti’s January, 2010 earthquake, for example, although it earned them virtually no media coverage. The highly publicized U.S. hospital ship that anchored off Haiti, the USNS Comfort, performed 843 medical operations; Cuba’s medical brigades performed 6499. Meanwhile 547 Haitians graduated from Cuba’s Latin American School of Medicine between 2005 and 2009, and more will continue to graduate year after year.

Third, and the main focus of this book, Cuba sends physicians and other health care professionals to Venezuela in return for much-needed oil. Cuban medical practitioners work and live in Venezuela’s barrios. From 2004 to 2010 one Cuban program “continually deployed between 10,000 and 14,000 Cuban doctors and 15,000 to 20,000 other Cuban medical personnel—dentists, nurses, physical therapists, optometrists, and technicians,” to work among the poor. In the barrios the Cuban health care workers practice primary health care, and promote a holistic and preventative approach—Medicina Integral Comunitaria (MIC), or Comprehensive Community Medicine (a concept, Brouwer notes, that appealed to health experts and some medical schools in Canada and the U.S. when first proposed 1978, but that was abandoned in the pursuit of profits in ‘health care markets’).

Cuban doctors work directly with Venezuelan medical students in the morning; the students take medical classes in the afternoons. The medical training, which is state of the art, is extremely demanding. Yet large numbers of Venezuelans—30,000 as of 2011, including many of the poor who have longed to be doctors but have never had the chance because of the huge cost of medical education—are now studying to be doctors.

Most want to practice as the Cubans do: meeting the needs of low-income people in the low-income communities long neglected by the Venezuelan medical establishment; promoting a holistic and preventative form of medicine; and working in the context of the values that are a central part of Cuban medical practice.

Time and again Brouwer recounts examples of the egalitarian values that guide the Cubans’ medical practice. He describes the shameful policy implemented in 2006 by George W. Bush, called the Cuban Medical Professional Parole Program. It is aimed at inducing Cuban medical personnel practicing grassroots medicine in poor communities in more than 100 countries to defect. Brouwer estimates that a mere 2 percent of Cuban medical personnel practicing outside Cuba have accepted offers of much more money. The rest, the vast majority—not the Occupy Movement’s 99 percent, but a close 98 percent—reject these monetary inducements. They believe in what they are doing, and in the values that are such a central feature of their practice.

We wonder if Cuba’s world class medical emergency team should be invited into Attawapiskat and other Aboriginal communities in which Canada has long violated residents’ human rights. (The Cuban team was poised to assist victims of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans in 2005. George W. Bush, whose lackadaisical response to Katrina is well known, rejected the offer. Would Prime Minister Harper similarly refuse a Cuban offer?) We wonder why many more Canadians are not being trained—without amassing huge debts—to become doctors, so that all Canadians who need health care can receive it, and all Canadians who want to do meaningful work, and who have the necessary abilities, can do so. We wonder why the values that inspire Cuban doctors and health workers—and that inspired the creation of our Medicare system in Tommy Douglas’ Saskatchewan—can’t be adopted by governments and the medical establishment in Canada.

We don’t know what is likely to happen in Cuba in the future. But for over half a century and against overwhelming odds, Cuba has developed educational and health care systems that stand head and shoulders above anything practiced elsewhere in the Americas, including the U.S. and that are a tangible expression of a system committed to the egalitarian principles of developing the capacities and capabilities of all people.

In these hard times, this book and the work it describes are an inspiration for everyone seeking alternatives to the dominant values and practices in our health care system, and in Canadian society generally.

Errol Black and Jim Silver are members of the CCPA-MB board.

by Dave Hall

October 26, 2011 was the deadline for developers to make proposals for seven large pieces of prime real estate scattered across Winnipeg. Unsurprisingly there were lots of proposals, although the City won’t let us see them yet.

The potential sale of so much public space should be of great concern to Winnipeggers. Why sell it? Who wins and who loses? What alternatives may there be to selling these properties? These questions need to be answered before any decisions are made.

The lands under the hammer are seven City owned golf courses: Windsor Park on the Seine River; Crescent Drive, Canoe Club and Kildonan Park on the Red River; and John Blumberg on the Assiniboine River, as well as Harbourview in North Kildonan and Tuxedo across from Assiniboine Park. Taken together, they are the most attractive opportunities Winnipeg developers have seen in decades. It doesn’t take a property developer to imagine the upmarket condos on the riverfront lots, or the suburban housing across from Assiniboine Park, or even the new strip malls or shopping centres. There’s clearly a lot of money to be made.

The decision to sell off these urban green spaces we have collectively owned for decades and in some cases almost a century flows from a consultant’s report commissioned by this administration. The report concluded that “Winnipeg has a surplus of open park space…” and that “…surplus property can…be sold for commercial or residential development.” It’s not clear what ‘surplus’ green space means, but it is easy to know what ‘sold for commercial or residential development’ means. And it won’t be low income housing or rental accommodations for the working poor.

Our current Mayor and Council were eager to hear this song. They responded by putting out requests for “Expressions of Interest” for the use and development of these seven properties. In various statements in Council and to the media, the City’s leading politicians and administrators have made clear that they have in mind the sale of the properties for commercial and residential development.

Little more than a month to put together proposals and a $50,000 deposit requirement ensured that the process didn’t get cluttered up by proposals from sports associations, golfers, community clubs or naturalists. In fact, it appears that only the Nordic Ski Association, which currently operates out of the Windsor Park Golf Course, made a non-commercial proposal.

Mayor Katz and Chief Administrative Officer Phil Sheegl have argued that selling the property would bring in cash that could be used for other good purposes as well as increase the tax base. Both are doubtless true, at least in the short term. The same could be said for selling every inch of green space in Winnipeg.

The question is why sell these properties and why now? Perhaps they hoped there would be little sympathy for golfers. Perhaps they think Winnipeg has become so poor under their guidance that we can no longer afford the amenities that we could afford in the 1920s or 1960s, when these courses were built. Perhaps they just see a once in a lifetime opportunity for someone to make a stack of money off a quick sale of some prime real estate. Not themselves, of course, but perhaps they can think of people who would like to do this.

For residents and wildlife, these are priceless community resources. And there is no doubt that any decision to sell and develop these lands will be permanent. Once they have been built on, there is no way future generations will be able to afford to buy them back for recreational use.

But there is another approach. Instead of asking who we should sell them to, we could ask some different questions first. And instead of limiting the discussion to developers and City Hall, we could involve the community in finding answers.

Are golf courses the best use of these lands? If they are to remain golf courses, can we find more imaginative mixed uses – such as the Nordic Ski Club’s use of the Windsor Park course in the winter? Could the courses be modified to make them friendlier to wildlife, hikers and riparian ecosystems? Just thinking about these questions shows how outrageous the City’s plans for these urban gems are. It’s good to periodically review our common possessions, such as these golf courses and rethink how we use them. But that is the discussion we should be having as a community.

Let’s have some real consultation, where all of us have a chance to put forward suggestions, so we can be proud when we pass these lands on to future generations. Let’s look at ways to make them the focus of healthy communities, where people want higher densities, because it allows easy access to such wonderful green spaces. And let’s look at how to create opportunities for new housing through developing some of the decaying or abandoned commercial and industrial areas of the city, even – dare we dream it – the Weston Rail Yards.

A local group has been formed to fight for just such a public discussion. Outdoor Urban Recreational Spaces (OURS) is fighting this attempt to sell off these urban jewels on the quiet. They are gathering signatures calling for a halt to these sales until a proper community discussion can take place. Anyone interested in OURS or their petition can find them at: www.ours-winnipeg.com.

This proposed sell off will not survive a public debate. Only slipping it through quickly and quietly will work. It’s up to Winnipeggers to react fast enough to stop to it.

Dave Hall is retired, and spends his time enjoying family, friends, and Winnipeg’s green spaces. He doesn’t use a golf club in his walks, but understands those who do.

For a full copy of the State of the Inner City report, click here.

Yesterday the CCPA-MB launched its seventh State of the Inner City report, entitled Neoliberalism: What a difference a theory makes.

The report examines the policy context that structures life in the inner city with a focus on three key areas: Employment and IncomeAssistance (EIA), housing, and second-chance education programs.

About 100 people attended the launch, which was held at Thunderbird House. A panel made up of Marianne Cerilli (West Central Women’s Resource Centre), Haven Stumpf and Kim

Embleton (Urban Circle Training Centre), and Kathy Mallett (Community Education Development Association) spoke to the report, explaining what they see as the impact of neoliberal policies on day-to-day operations and on the people they serve.

Shauna MacKinnon moderated the discussion, after which Together We Have CLOUT, a film about the inner city coalition Community-Led Organizations United Together (CLOUT), was screened.

Shauna MacKinnon moderated the discussion, after which Together We Have CLOUT, a film about the inner city coalition Community-Led Organizations United Together (CLOUT), was screened.

Today, EIA rates are extremely low, quality affordable housing is increasingly hard to find, and second-chance education programs struggle with inadequate funding. For inner-city communities, these are daily realities that are directly influenced by the neoliberal approach to policy-making.

by Lynne Fernandez

Two issues of concern have recently arisen at City Hall – the twenty-cent transit fare hike — just passed by council — and a new policy to share water and sewer services with exurban municipalities. Both issues are of note for three reasons: there will be significant financial implications for Winnipeggers; they will encourage unsustainable, environmentally damaging behaviour and, the means by which these policies are being implemented lack transparency and thwart any sort of democratic process.

We contrasted these developments with the recommendations by the City’s own citizen consultations in the Call to Action report. The report reflected a strong commitment to community; the belief that growing economic inequality is unacceptable; and, the understanding that modern cities must reverse environmentally unsustainable growth patterns. The voices of those who participated in this report were included in the City’s final municipal development plan, Our Winnipeg, which sets the course for future development. Our Winnipeg is premised on commitments to environmental sustainability and complete communities.

The 40,000 Winnipeggers who participated in the Call to Action will be disappointed to learn just how far the City is deviating from their desires and recommendations. Report participants expressed a strong preference for:

- Commuting responsibly by expanding rapid transit and human-powered traffic;

- Enhancing urban spaces through increased urban density, preservation of agricultural land, development of pocket parks and expanding local businesses;

- Switching to “smart” infrastructure to reduce costs and stress on the environment. Natural systems could include storm and waste-water filtration;

- Working to bring all Winnipeggers to an acceptable living standard through access to essential services and promotion of strategies like urban gardens.

In what appears to be a return to outdated city planning ideas, the City is thumbing its nose at all of these preferences.

Council’s continued flip-flopping with provincial and federal officials is responsible for the lack of funds to complete rapid transit, making its insistence on passing the cost to low-income earners mean-spirited and counterproductive. The twenty-cent transit fare hike will not only discourage people from taking public transit, it will actually prevent many — who cannot afford a car — from being able to move about the city. So in one fell swoop council has managed to undermine any movement towards responsible commuting, and cut marginalized Winnipeggers from access to an essential service: transportation.

In order to ensure that low-income Winnipeggers would have access to reliable transportation to get to school, work, medical appointments, recreational centres — in short, to live their lives — the City should be lowering transit fares for them. The city could sell low-cost tickets to the provincial government so it could then distribute them to Winnipeg social-assistant recipients.

The proposed policy (to be voted on by council on December 14) to grant authority to CAO Phil Sheegl to negotiate with exurban municipalities for the expansion of City water and sewer services represents yet another step away from the kind of development Winnipeggers want. First of all, deals of this sort may have significant impact on Winnipeg’s revenues and development patterns, two concerns which should fall under the watchful eye of city councilors who are elected to protect our best interests. By removing their ability to learn the details of future contracts and debate their implications, there will be no transparency or oversight to ensure these deals make financial or environmental sense. Winnipeggers should be worried on both counts.

Many people move from Winnipeg to municipalities like West St. Paul so they can enjoy more luxurious homes while paying lower taxes. Most of these people still work in Winnipeg and so use our infrastructure heavily without contributing to its upkeep by paying taxes to the City. Although we do not yet know what sort of costing will be offered to these municipalities, it is likely that they will be able to “free ride” on Winnipeg’s lower costs to provide water and sewer services without contributing a fair portion for its upkeep. So not only do Winnipeg tax payers end up subsidizing exurbanites, but our tax revenues diminish every time a Winnipegger relocates. Without elected official oversight, we just don’t know if these deals will be a win-win situation for exurbanites, and a lose-lose situation for the rest of us.

Modern cities should be increasing density and preserving surrounding farming and wild areas. This proposed policy will make it easier for bedroom communities to flourish and enlarge our environmental footprint. More cars will commute back and forth on more regional roads, and fewer people will use (and contribute to) less-polluting public transit. It is unlikely that these contracts will have a mechanism to encourage conservation of water, thereby allowing the municipalities to drain precious resources even further.

The 40,000 Winnipeggers who participated in the Call to Action and Our Winnipeg consultations were hopeful that the City would take concrete action towards a more sustainable, democratic, equitable and modern city. If these two policies go through, the City will go a long way to making sure that doesn’t happen.

Lynne Fernandez is a political economist with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives

For a PDF version, click here.

by Shauna MacKinnon

There has been much progress in addressing the issues facing Winnipeg’s inner city in recent years, but there remain many challenges. This reality frustrates no one more than those individuals working on the front lines with people who continue to be deeply affected by poverty.

Many people have committed their lives to improving the inner city, some for decades. It deeply saddens them to see that in spite of their best efforts, life seems to be worse for many individuals and families than it was thirty years ago. But they also recognize that their efforts can only go so far. They know that what happens in the broader social and political context has implications for individuals and families. They know that what is most needed right now is a significant change in public policy, beginning with a commitment by governments to invest in people sufficiently and over the long term.

By Errol Black

Yesterday, December 7, Justice Douglas Campbell ruled that “Agriculture Minister Gerrry Ritz broke the law by failing to put the matter [of the future of the Canadian Wheat Board – Bill C – 18] to a farm vote first.” The ruling confirmed that the opponents of Bill C – 18 (farmers, directors of the CWB, and the opposition parties) are right and the Harper government is wrong.

Ever since this round of the debate on the future of the CWB was initiated, Harper and Ritz have insisted that they would break the monopoly of the CWB and create an open market for wheat and barley – regardless of the law. In response to Justice Campbell’s ruling Ritz said: “I can tell you that, at the end of the day, this declaration [by the court] will have no effect on continuing to move forward on [grain marketing] freedom for western Canadian farmers. Bill C-18 will pass.”

Ritz’s reaction confirms yet again that Harper and cabinet bullies like Ritz believe themselves to be above the law. This tendency is very worrisome; in the words of the Honourable Justice Campbell:

When government does not comply with the law, this is not merely non-compliance with a particular law, it is an affront to the rule of law itself […].

The question is: what can citizens do to convince the Harper government to comply with the law and put the issue of the future of the CWB to farmers?

Unfortunately, given the Harper government’s contempt for the rule of law and its reckless habit of disregarding the wishes of Canadian farmers in particular and Canadians in general, we should be concerned about the sorts of legislation and policy changes that we’ll be confronted with in the immediate future.

To date, virtually every action of this government is based on promises and commitments that originate with the National Citizens Coalition – under Harper’s leadership – and the Reform Party, including:

- Abolition of the Long-gun registry;

- The omnibus crime bill (Bill C -10);

- Tax cuts for big corporations;

- Anti labour interventions in collective bargaining in the federal jurisdiction; and

- A repudiation of Kyoto and measures to limit the assault on our environment.

The one thing that is common to all of these actions is that they cannot be justified on the basis of factual or analytical evidence. Indeed, the Harper government doesn’t even bother to try and justify these actions. Listen to Minister Toews on Bill C – 10, for example, or Labour Minister Raitt on the anti-labour interventions.

Other matters in the works that are suspect are the austerity measures initiated by Finance Minister, Flaherty, and the expanded role for Canada’s military in combat interventions under the auspices of NATO and the U.S.

The destruction of the Canadian Wheat Board has direct and obvious implications for Manitoba, but we also need to understand the negative impact Harper’s other policies will have on us. Bill C10 will dramatically increase the provinces’ spending on jails and do nothing to make us safer (with the added effect of decreasing spending on essential services); the coming austerity measures will further decrease revenues and provide justification for cutting of all kinds of social programs.

Did those Canadians who voted for Harper understand who/what they were voting for? Did they knowingly bestow such power? What were they thinking?

For the sake of us all, I hope they are having second thoughts.

Looking for information about housing in Winnipeg? Look no further – here you’ll find all kinds of facts and statistics about housing in Winnipeg and Manitoba.

References are available at the bottom of the page, in case you are looking for more details.

Core Housing Need

Definition of Core Housing Need

“Acceptable housing is defined as adequate and suitable shelter that can be obtained without spending 30 per cent or more of before-tax household income. Adequate shelter is housing that is not in need of major repair. Suitable shelter is housing that is not crowded, meaning that it has sufficient bedrooms for the size and make-up of the occupying household. The subset of households classified as living in unacceptable housing and unable to access acceptable housing is considered to be in core housing need.”(1)

Core Housing Need

In 2006: (2)

- 11.3 % of all MB households lived in core housing need (46,900 people)

- 24.0 % of MB renter households lived in core housing need (28,800 people)

- 6.2 % of MB owner households lived in core housing need (18,100 people)

- 22.3 % of those who immigrated to Canada between 2001 and 2006 lived in core housing need in Manitoba (1,600 people)

In 2006: (3)

- 37.3 % of Winnipeg tenant-occupied households spent over 30% of their income on housing.

- 11.6 % of Winnipeg owner-occupied households spend over 30% of their income on housing.

Renting in Manitoba

Current Vacancy Rates

In April, 2011, the vacancy rate was (4)

- 0.7 % in Manitoba, the lowest vacancy rate in the provinces

- 0.7 % in Winnipeg

- 0.5 % in Thompson

Winnipeg’s Rental Universe

(This data only applies to apartment buildings with three or more units)

The rental universe in Winnipeg (5)

- has declined in 15 of the past 18 years.

- Lost 835 rental units, of which at least 450 units were permanently removed from the rental universe, between October 2009 and October 2010 (leaving 52,319 units).

Since 1992, Winnipeg’s rental universe has declined from 57,279 units to 52,319 in 2010, a decline of about 9 percent (6). At the same time, the population of Winnipeg has increased from 677,000 to 753,600, an increase of about 11 percent (7).

- The result is a drop in the number of rental units per 100 people from 8.5 units to 6.9.

Rents

In April 2011, the average rent was (8)

- $718 in Manitoba (compared with 696 $ in April 2010)

- $725 in Winnipeg (compared with 703 $ in April 2010)

- $692 in Thompson (compared with 652 $ in April 2010)

In 2011, the Median Market Rent in Manitoba was: (9)

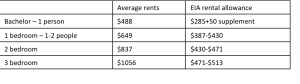

Affordability of Average Rents in Winnipeg (10)

EIA and Rent in Winnipeg (11 and 12)

Social Housing

Manitoba Housing “owns the Province’s housing portfolio and provides subsidies to approximately 34,900 households under various housing programs. Within the portfolio, Manitoba Housing owns 17,600 units of which 13,100 units are directly managed by Manitoba Housing and another 4,500 units are operated by non- profit/cooperative sponsor groups or property management agencies. Manitoba Housing also provides subsidy and support to approximately 17,300 households (including 4,700 personal care home beds) operated by cooperatives, Urban Native and private non-profit groups.” (13)

Demographics

Migration

In 2010, 15,803 international migrants came to Manitoba, and 12,340 immigrants moved to Winnipeg. (14)

The population of Manitoba increased by 15,800 people from 2009-2010 (from 1,219,600 to 1,235,400). (15)

The population of Winnipeg increased by 9,700 people from 2009-2010 (from 674,400 to 684,100). (16)

National Social Housing Construction

In 1993, the federal government withdrew from housing. Until then, about 10 percent of the housing built each year in Canada was affordable to lower income households; since then it has been less than one percent. (17)

Sources

(1) CMHC 2011, Canadian Housing Observer.

(2) CMHC 2006, Canadian Housing Observer. Also offers data on types of family, Aboriginal status, and period of immigration.

(3) City of Winnipeg 2006. 2006 Census Data – City of Winnipeg.

(4) CMHC 2011. Rental Market Report: Manitoba Highlights.

(5) CMHC 2011. Rental Market Report: Manitoba Highlights.

(6) CMHC 2011. Personal communication from D. Himbeault.

(7) City of Winnipeg. 2011. Population of Winnipeg.

(8) CMHC 2011. Rental Market Report: Manitoba Highlights.

(9) Government of Manitoba, date unknown. Housing Income Limits and Median Market Rent

(10) CMHC 2010. Winnipeg CMA Rental Market Report

City of Winnipeg 2006. 2006 Census Data.

(11) CMHC 2010. Winnipeg CMA Rental Market Report

(12) Government of Manitoba. Employment and Income Assistance Facts.

(13) Manitoba Housing and Community Development. 2010. Annual Report 2009-2010.

(14) Government of Manitoba. 2011. News and Resources.

(15) City of Winnipeg. 2011, May 1. Population of Winnipeg.

(16) City of Winnipeg. 2011, May 1. Population of Winnipeg.

(17) CMHC. 2011. CHS – Public Funds and National Housing Act (Social Housing).

CMHC. 2011. CHS – Residential Building Activity.

This year’s State of the Inner City report examines the impact of neoliberalism on Employment and Income Assistance, housing, and second-chance education program policies in the inner city. The report will be released on December 14 at Thunderbird House; look here for more information.

As has been the case every year for the past seven years, our community partners set a clear direction for us to follow as we moved forward with this year’s State of the Inner City Report. In past years our partners were most interested in telling the positive stories while also pointing out where policies might be improved. But things took a bit of a different turn this year.

Although initially the focus for this year’s report was on education, at a second meeting the discussion moved us in a different direction. One participant raised concerns about the unreasonable expectations placed on community organizations. She described the devastation she sees around her that has resulted from growing poverty and inequality. She described what she believed to be a failure on the part of all levels of government to do what is necessary to resolve this problem.

The discussion became lively as other participants jumped in, affirming her frustration.

Follow us!