First published in the Winnipeg Free Press December 12, 2020

By Lucille Bruce

“STAY home.”

For months we have heard this refrain from our public-health officials. And yet, in Winnipeg, hundreds of people have no home. As a result, they are particularly vulnerable to COVID-19. A large majority are Indigenous.

Winnipeg is home to Canada’s largest urban Indigenous community. More than one-third of Manitoba’s Indigenous population lives in the province’s capital; Indigenous people make up just over 12 per cent of Winnipeg’s residents. However, Indigenous people face rates of poverty twice as high, and rates of homelessness six times as high, as the average in our city.

These statistics are an outcome of 150 years of government policies that suppressed Indigenous peoples’ traditional economic, cultural and governance institutions, seized Indigenous lands for resource extraction and separated children from their families with the goal of forced assimilation. Reserve and scrip systems, forced migrations, residential schools, the ’60s Scoop, CFS policies, as well as chronic underfunding of public services and infrastructure in Indigenous communities, have resulted in intergenerational trauma, family separations and systemic poverty, leading directly to Indigenous peoples’ experiences of homelessness in Winnipeg today.

In the context of COVID-19, homelessness is a recognized public-health risk. While we don’t have disaggregated data on COVID-19 for housing status, we know that community transmission, surging case numbers and high test-positivity rates affect those experiencing homelessness, most of whom are Indigenous.

We know that those experiencing homelessness have higher rates of complicating health factors and disabilities that can place them at greater risk of severe outcomes from COVID-19. We also know that First Nations account for just over 10 per cent of Manitoba’s population yet make up more than one-quarter of COVID-19 hospitalizations and nearly half of those in ICU.

Our crisis of homelessness, which disproportionately impacts Indigenous people, is worsening the impacts of COVID-19. Most services available to those without a home have been delivered in congregate settings, where risk of transmission for COVID-19 and other respiratory viruses can increase in winter. While the homeless-serving sector has collaborated on a strong COVID-19 response plan, with robust prevention measures for shelters and drop-ins, some people will face barriers to accessing these services.

Others may be afraid to, perceiving a risk of catching COVID-19. Now more than ever, emergency shelters and temporary warming centres cannot meet everyone’s needs. Permanent housing options are the only answer.

Cities that have been successful in reducing and ending homelessness have done so by ensuring an adequate supply of housing to meet community needs. As we learned from the Winnipeg Comprehensive Housing Needs Assessment, released by the City of Winnipeg earlier this year, more than 700 affordable housing units will have to be created each year for the next decade to address that need in our city.

To be effective at ending homelessness, new housing must also meet the specific needs of Indigenous people and those who experience homelessness. What does this look like?

Over the past year, End Homelessness Winnipeg has partnered with other Indigenous organizations on a range of Indigenous-led housing initiatives that provide a clear vision. A collaboration led by Wahbung Abinoonjiaag, with local women’s and Indigenous organizations, has developed plans for a transitional housing complex that will support women and families fleeing violence and at risk of homelessness, with suites designed to accommodate larger families and support family reunification.

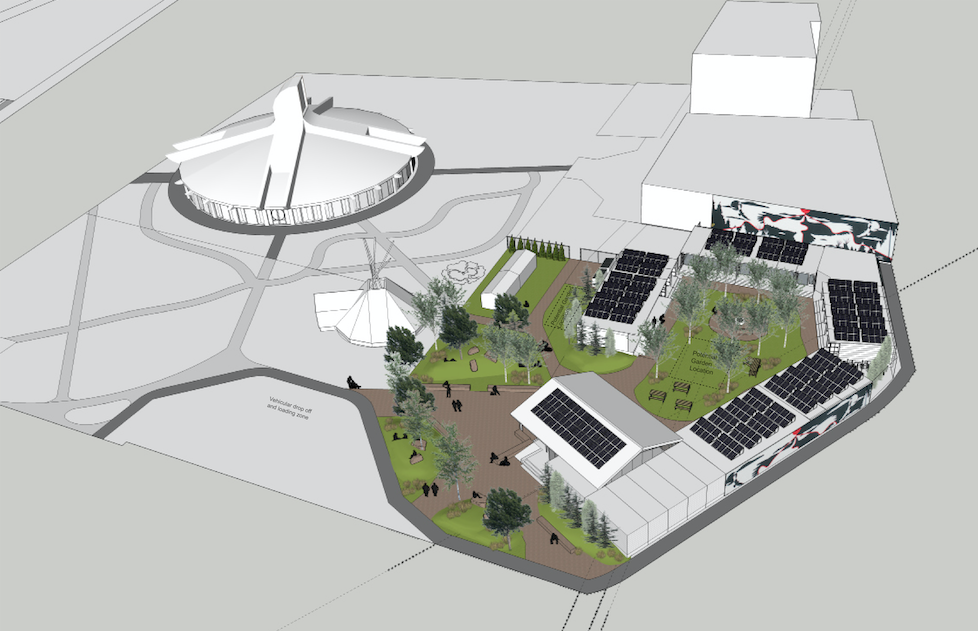

The Village project, led by Ma Mawi Wi Chi Itata Centre and supported by six other Indigenous organizations, including End Homelessness Winnipeg, has consulted directly with people living in encampments to design a constellation of tiny homes in a supportive community, guided by Indigenous Elders, with services based on Indigenous values and approaches.

A North End Housing Lab, in partnership with the Winnipeg Boldness Project, has identified four key prototypes to address housing need in the city’s North End: Indigenous-led housing ventures, Indigenous models of housing, zoning and regulation improvements, and social finance for development.

These projects all point to the same conclusion: Indigenous-led approaches that centre the needs of people experiencing homelessness are required to address the interrelated crises of Indigenous homelessness and COVID-19 in Winnipeg. It is unacceptable, in the era of Truth and Reconciliation and the Calls for Justice for Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, that Indigenous people should continue to face systemic barriers to securing housing, which is a basic human right.

Safe, affordable housing that is designed, developed, delivered and managed by and for Indigenous people is the starting point for fulfilling the right to housing of Indigenous people. It is also an essential step toward health equity in the context of COVID-19. More than this, it is a matter of life and death.

Lucille Bruce is the president and CEO of End Homelessness Winnipeg.