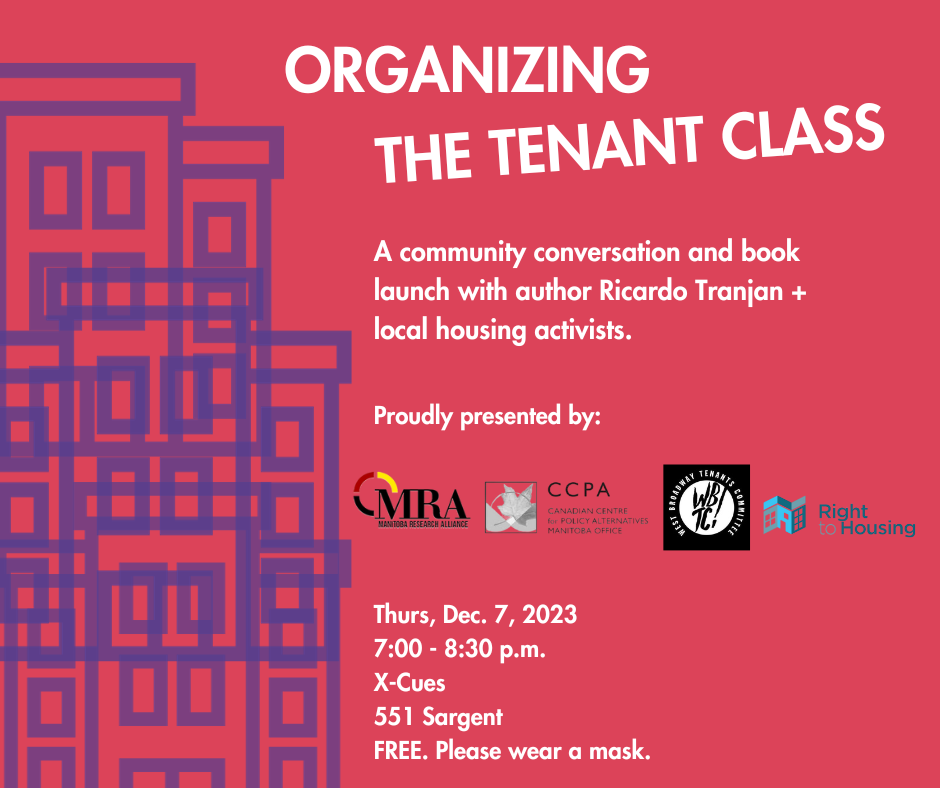

Ricardo Tranjan, author of The Tenant Class, joins us for a community conversation with local housing activists Rebecca Hume (Together at 149 Langside), Yutaka Dirks (R2H Coalition) and moderator Stefan Hodges (West Broadway Tenants Committee).

In celebration of the event, Ricardo spoke with Amanda Emms, community researcher and West Broadway Tenants Committee member. Their conversation has been edited for clarity and length.

Tell us a little bit about yourself.

I’m a political economist with the Canadian Center for Policy Alternatives. Been here for about five years. Before that, I worked for the City of Toronto. I was the policy lead and eventually the manager of the city’s poverty reduction strategy. Before that, I was doing academic work mostly focused on the economic and political developments in Brazil, where I grew up.

You kick off The Tenant Class explaining why there is no housing crisis. Give us an idea of what to expect at our upcoming event through this lens and who might be interested in attending.

So by saying that there’s no housing crisis, in no way I mean to belittle the really concrete hardship that a growing number of people are experiencing. But I invite us to challenge that we have a crisis. When you think about a crisis, we tend to think about something that is unexpected. We tend to think about something that impacts everyone negatively. We tend to think about something everyone is interested in and solving because we want the crisis to go away. That way of thinking prevents us from having a more clear-eyed look at the housing question in Canada and paying more attention to the fact that there’s actually a group that is enormously benefiting from the situation the way it is.

We’re talking about the real estate industry, all the financiers, a lot of homeowners whose housing value has grown exponentially over the past couple of decades. And the people who are negatively impacted are tenants or people who are unhoused, people who are now preparing for the winter and the large and growing encampments that I’ve seen across the country now in small, large and medium cities. Also to understand that some folks are actively engaged in keeping things the way they are, or lobbying governments to make things worse because there’s so much money to be made out of this and they want to cash on that money.

So that’s what the challenging of the housing crisis is meant to do. It’s to invite us to have a clearer understanding that what we have here is a class struggle between those trying to make as much money as possible out of land and housing and those trying to be securely housed.

So what are we expecting at the event? What the book does is provide this alternative perspective on the housing crisis. Then, it shines a light on tenant movements, past and present, and all the great work that tenant movements have done, the really hard work of organizing and carrying out this sort of frontline political struggle. I’m hoping this event will do something similar. It’s providing that alternative framing, then turning the spotlight to those folks carrying out the political struggle and then on all of us to think about how to support them. That’s what we have done in past events in Toronto, Vancouver, Hamilton and elsewhere. So that’s what I’m hoping that we do in Winnipeg.

You talk about how we have an almost obsessive view of home ownership in Canada. We equate owning a home with this idea of “making it.” What are some myths behind this thinking and how does it strip away the securities of people who rent?

Yes, the fundamental issue is that in Canada, housing security is associated with ownership. Folks are obsessed with buying a house for two reasons. One is that, it’s not that they love spending their Sunday fixing the basement, it’s that we equate owning with housing security. That makes sense because tenant protections are so weak. If you move to a new hood and sign your kids up for school and extracurricular activities, you start hanging out with friends and building a community, you hope you’re not going to get kicked out. You want your kids to go through the same school and to have friends and to build a network.

So people build communities. They get attached to an environment and they want to be able to be there. They want to have their kids grow up there. They want to age in place. We associate housing security with owning and not with renting because tenant protections are pretty weak. We know that if you rent, you can be kicked out overnight. So I think that’s the shift. But there’s a second piece of it, which is status. Homeowners have more status than renters. Renters are by and large seen as people who didn’t make it, didn’t work hard enough in the classic North American “Pull yourself by your own bootstraps” kind of thing. So those negative perceptions about tenants are important to address for one, because they’re false. Second, they prevent us from having a broader conversation about governments, what secure tenancy looks like and how to have policies that allow it.

Third, from a political perspective, it is hard to build a strong social movement around a stigmatized identity. So when you look at a number of social movements, past and present, one of the first kinds of political work we need to do is make people feel more comfortable with that identity, own it and not be ashamed of it. That helps the movement-building phase of things.

In one chapter, you take a lot of care to show readers how tenant organizing is not new. It’s been a constant in Canada but often overlooked in our history books. Can you talk about your motivation behind this and what it will take for organizers to be more at the forefront of history moving forward?

It is extremely important for us to revive the history of common people, the history of popular movement and the successes of social movements. It is extremely important to keep the economic elites from telling their version of history, which is always them owning everything and making sense of everything for everyone else. We cannot let the elites own history. We have to tell history as it is and we need to talk about and celebrate the real history. The history of common people and the history of popular movements. The revival in that history can have a positive impact in motivating movement and class action.

In a way, it’s my reason for writing the book. I’m not an organizer and I don’t pretend to be. I’m a researcher and writer. The book was my way of contributing to the movement, particularly some of these accessible and short texts. For others in a similar position like myself, doing policy research, media, or communications work, I think we should bring forward the unmediated perspective of tenant organizers and movements instead of always going to the policy wonks or a mediator who’s speaking on behalf of. We see that quite a bit and this shift would be great. So that’s what I try to do in my work instead of ever speaking for organizers. I try to kind of create space from that perspective within the spaces that I write as a policy research writer.

Throughout the country, tenants are organizing in solidarity against the landlords who profit off them. Yet, as you point out, there is still so much pushback against presenting landlords as part of the problem. What is going on here and how can this perception be dismantled?

Housing is about land. I hope the housing struggle can help us build a bridge and come up with concrete ways of talking about colonization and decolonization because fundamentally we’re talking about markets that were deliberately created through the expropriation of land, through various crimes, including genocide, to facilitate profit-making and wealth accumulation, and to the benefit of only a few. Markets don’t come out of thin air. They’re created. An active part of the colonization process is to create those markets. Hopefully, thinking about how the colonial project involving the very deliberate creation of these markets creates opportunities for us to understand how that structure favours very few to the detriment of many.

Is there anything else you would like to add?

There’s that short and final chapter of the book when I talk about picking a side. I’m having a lot of conversations about what that means. How can we shift what we do away from the never-ending policy debates to movement-oriented political action? How can we make that shift in concrete ways? Not only individually, I’m talking about organizations shifting their focus so that we put up a political fight. And we fall less into the trap of forever discussing policy tweaks as if policy design was the missing link. It’s not. That chapter is my way of inviting folks for that conversation.