By Josh Brandon

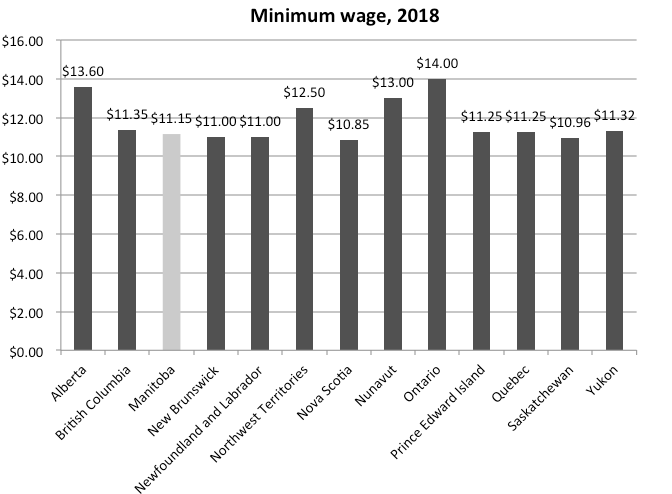

As we roll into 2018, low income Manitobans are falling further behind. While minimum wage in Ontario went up on January 1 to $14 per hour, in Manitoba it is stuck at a poverty level of $11.15 per hour. This leaves minimum wage workers up to $5,700 per year behind their Ontario counterparts. Here, a single parent with one child earns as much as $7,000 below the poverty line. Manitoba has now fallen to 8th among provinces and territories in minimum wage.

This gap looks particularly stark when compared to the incomes of the wealthiest Canadians. The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives’ annual CEO pay survey showed the top paid CEOs in Canada made an average of $10.4 million last year. A minimum wage worker in Manitoba would need to work 466 years to earn as much as these CEOs did last year.

Bus fares in Winnipeg also shot up by 25 cents on January 1. This was the largest bus fare hike seen in several years in Winnipeg. The cost of a monthly pass increased by $10 to $100.10, increasing annual costs by an extra $120 in 2018. As transit becomes more unaffordable it will put transportation further out of reach for low income families, limiting their employment, training and education opportunities, curtailing their social inclusion and putting stress on their health. Winnipeg remains one of the few major cities across Canada without a low income bus pass.

Meanwhile, housing costs continue to rise. The median cost of a three bedroom apartment in Winnipeg reached $1,338, up nearly 5 percent from last year. To afford a median three bedroom, a family would need an income of at least $53,520. Affordable housing is out of reach for more than 40,000 Manitoba households.

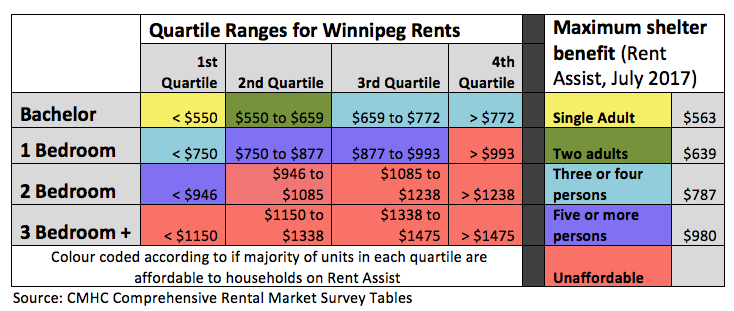

For households relying on Rent Assist, rent is becoming more unaffordable this year. Rent Assist provides a subsidy up to 75 percent of median market rent (MMR) for the size of unit required by the family. However, few units are available in the private market at this level of rent. The chart below divides rents for each bedroom size into quartiles – the cheapest 25 percent of units represents the first quartile, the next cheapest 25 percent the second quartile, etc. Using this analysis, we show how Rent Assist does not help many families afford the size of unit they require. For single adults, Rent Assist pays a sufficient amount for only the cheapest bachelor units. Larger families cannot afford larger units: the subsidies allocated for Rent Assist are only sufficient for a family of three or four to afford bachelor units, or some cheaper one bedrooms. Families of five or more can only afford the cheapest two bedroom units available on the market. As a result, most families on Rent Assist must choose between unaffordable rent and overcrowded housing that does not meet National Occupancy Standards.

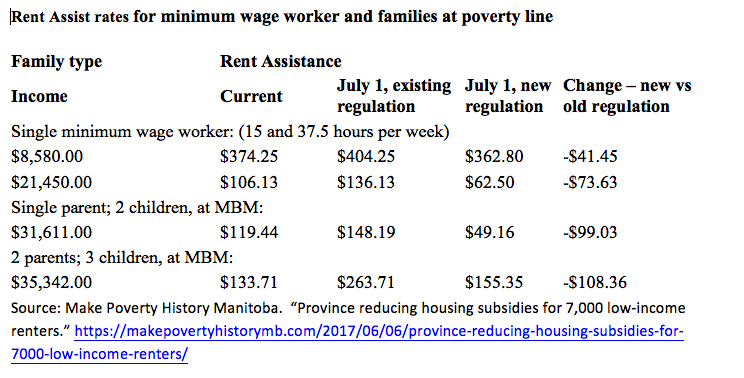

Last year, changes to Rent Assist and Manitoba Housing policy made housing even less affordable for low income renters. Rent Assist subsidies previously had been set at 75 percent of MMR minus 25 percent of household income. Last year the formula was changed to 28 percent of income. Likewise, tenants in Manitoba Housing had their housing charges increased to 28 percent of income. Previously, housing charges for Rent-Geared-to-Income were set at either 25 or 27 percent of income. These changes reduced benefits or increased rents by up to $100 per month.

Meanwhile, EIA rates for the poorest Manitobans are stuck at levels that were inadequate 20 years ago. Total incomes from all sources for a family of four on social assistance may be almost $500 below the poverty line. Individuals on general assistance receive as little as $195 per month for food, clothing, transportation and other basic necessities. As with rents and bus fares, the cost of these necessities rise each year, leaving the most vulnerable Manitobans thousands of dollars in the hole as they start their annual budget planning process.

The good news is there is an opportunity to make headway in reducing poverty in 2018. The Province has recently launched consultations for a Manitoba poverty reduction plan. This is the first step towards implementing a commitment the provincial government has promised since it was elected in 2016. Wisely, the Province has started these consultations by listening to people with lived experience of poverty.

Manitobans who live with poverty know firsthand how decisions like freezing minimum wage, cutting back on Rent Assist or raising bus fares are harmful. They know that every increase means they will be that much more reliant on food banks to make it through the month, or worse yet, more likely to lose their housing altogether. People in poverty can speak eloquently on how their social and economic isolation wears on their physical and mental health and can become a barrier to reaching the training and employment they need to escape poverty.

Manitoba needs a comprehensive plan with targets and timelines to lift all households out of poverty. The Province should listen to the participants in its consultations, as well as take notice of the research that has already been done by community organizations and government alike of the steps it must take to end poverty. One such resource, The View From Here (2015), offers 50 community supported recommendations for action. Following this community lead, the Province should reverse the cuts it made in 2017, while investing in housing, quality employment, income supports, mental health and child care. Only then will 2018 offer a light of hope for those living in poverty.

Josh Brandon is Community Animator at Social Planning Council of Winnipeg.