By Pete Hudson

One of the few silver linings in the monstrous shadow cast by COVID-19 has been the forced contemplation of the kind of society we would wish for when it passes, and the role of our governments in shaping it. One view is that the major role governments have played (or not) in controlling the spread of the virus and rendering assistance (or not) to those in need because of it, has demonstrated the need for a resilient, and adequately funded public sector, which ought to continue after the immediate threat has gone.On the contrary, goes the opposing refrain: the debt burden arising out of dealing with the crisis can only be managed by a drastic reduction in public services.

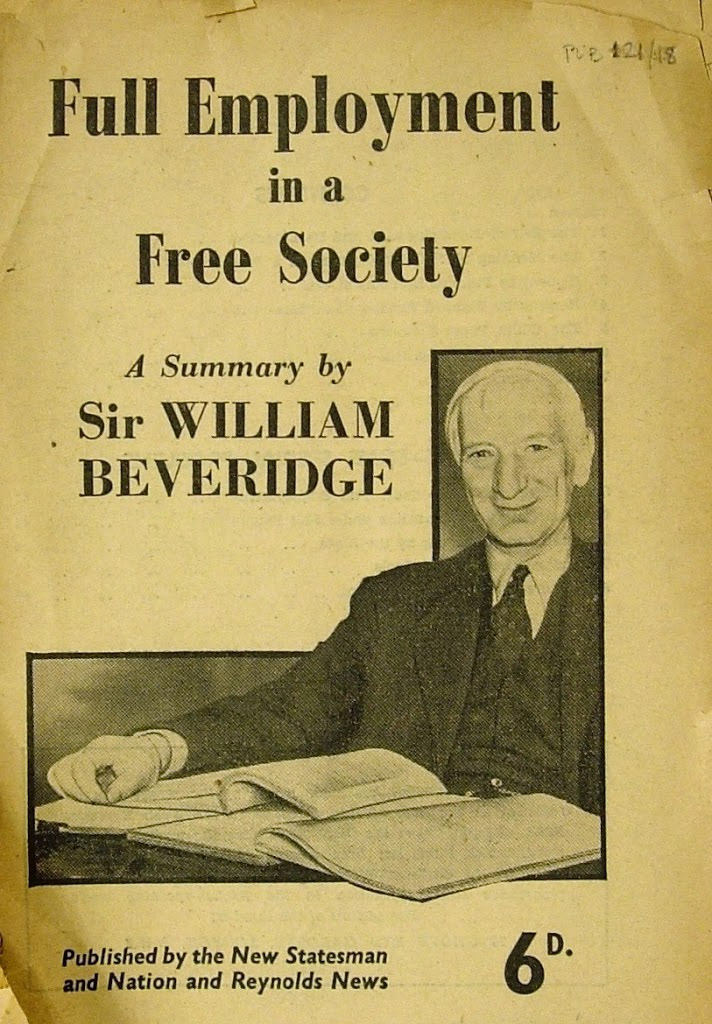

A glance at an earlier crisis advances the debate. During WWII, planning structures were established to develop a vision for a post-war nation. One of the documents to come out of that process in the UK was the Beveridge Report in 1942 (the 1943 Marsh Report in Canada followed very similar lines). The Report reminds us that the core debate is about values. Evidence enters the picture when determining what policies do, or do not, advance those values. On the values question Beveridge made the distinction between freedom to (do something such as dissent, or pollute) and freedom from. Beveridge emphasized the latter and identified five such freedoms. Freedom from Want was the basis for all of the post-war income supporting programs – unemployment insurance, workman’s compensation, public pensions, and the residual social assistance programs. Freedom from Squalor was the basis for a massive post-war affordable housing program. Freedom from Idleness meant the pursuit of full employment policies which included the expansion of the human services. Pursuit of Freedom from Ignorance involved accessible secondary and post-secondary education regardless of income, and Freedom from Disease created the National Health Service, providing a universal, comprehensive range of health and public health services free at the point of service.

On the issue of evidence, we need only study the example of today’s senior citizen population in Canada and the UK which, on average, is more financially secure, healthier, longer lived and better housed than previous generations. And is the connection between these positive outcomes and the post-war advancement of the five freedoms not evident? The attack on these freedoms in recent decades will mean a less fortunate next generation of seniors. And this might be especially true of Manitoba.

Freedom from Want? Manitoba’s Income Assistance program is deeply impoverishing, but the present government continues to erode it. The minimum wage is frozen and many other wages remain inadequate. Collective bargaining is weakened. Freedom from Squalor? Portions of already limited social housing stock have been sold off. Winnipeg has some of the oldest and most decayed housing in the country. Freedom from Idleness? The number of deliberately created unemployed, as opposed to unavoidable pandemic related unemployment, is already in the several thousands. Freedom from Ignorance? Access to post-secondary education becomes less affordable, while quality becomes ever harder to maintain. Freedom from Disease? The evidence on the hospital consolidation isn’t all in yet, but arbitrary cutbacks in expenditure, required by this government of the Regional Health Authorities, have undoubtedly led to greater difficulty accessing the system, especially primary care. Paradoxically, all of the foregoing is claimed as necessary to slay the deficit dragon by reducing expenditures, while past and proposed tax cuts reduce the revenues which, if retained, could achieve the same objective.

And the role of government? In Manitoba, part of the current government’s ideological package is that the private sector best meets society’s needs, despite evidence that low tax, small government is synonymous with the loss or absence of the programs which uphold the five freedoms.

The private sector has little interest in the social safety net. It deals with Want and Idleness only insofar as it incidentally creates employment. Even so, it strives for the cheapest labour possible and also sheds jobs without loss of sleep. It has demonstrated little interest in providing affordable housing. In regard to freedom from Ignorance and Disease, the for-profit sector is generally happy to enjoy the benefits of a healthy and educated workforce with a minimal responsibility to actually provide them, and even lobbies against helping to pay for them.

Giving an airing to values hidden beneath the surface of public policy debate is crucial to addressing the question of what should post-COVID look like. It would be instructive, for example if someone inquired of Manitoba’s current Premier if he approves of Lord Beveridge’s five freedoms. To say no would be the equivalent of a denouncement of Mother Theresa. A more likely response would be that we can’t afford them. But wait! In 1945, much of Britain was a pile of rubble and it shouldered a massive, war-incurred debt to GDP ratio of 250 per cent. Instead of using those two facts as excuses to slash public services, the government, as noted, took the opposite approach. Most citizens were experiencing positive outcomes within a decade, and the strategy continued until the late 1970s. Surprise! By 1975 the debt to GDP ratio was 55 per cent. Please don’t tell us that a similar strategy is not affordable as we emerge from the current crisis.

Pete Hudson is a Senior Scholar in the Faculty of Social Work, University of Manitoba, and a Research Associate with the CCPA – Manitoba.