By Sarah Cooper

Vulnerability to COVID-19 is not shared equally. The past year has shown that those who are most vulnerable to COVID-19 are those who live in poverty, in overcrowded housing, or in poorly regulated privately-owned and operated personal care homes. As Damian Barr said about the pandemic last year, “We are not all in the same boat. We are all in the same storm. Some of us are on super-yachts. Some have just the one oar.”

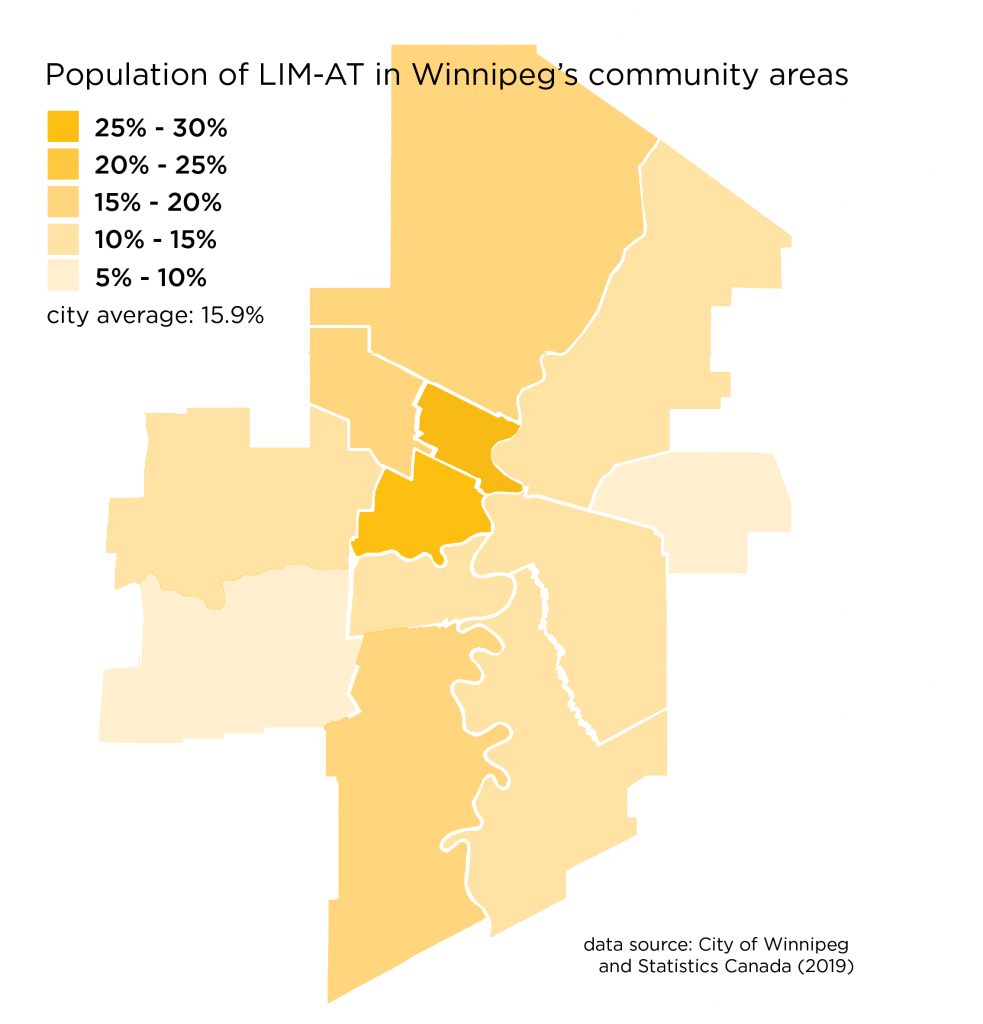

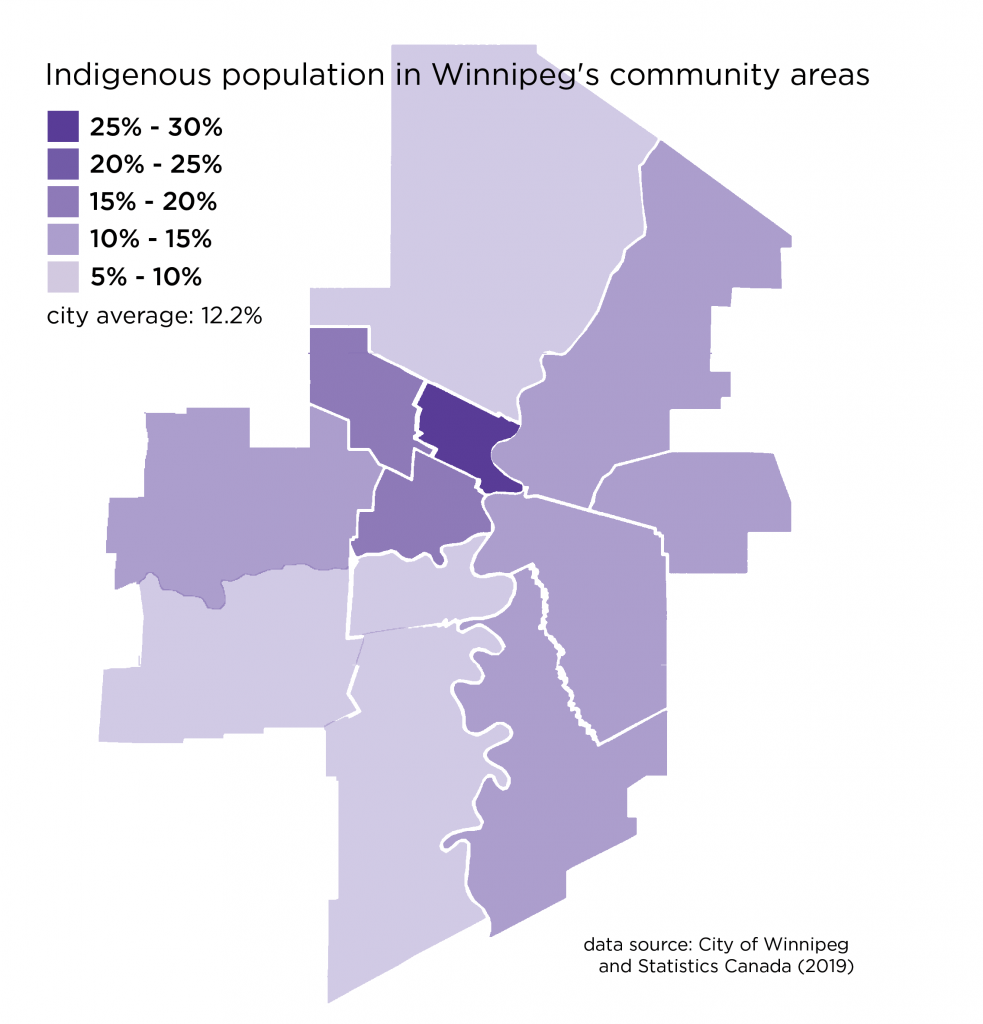

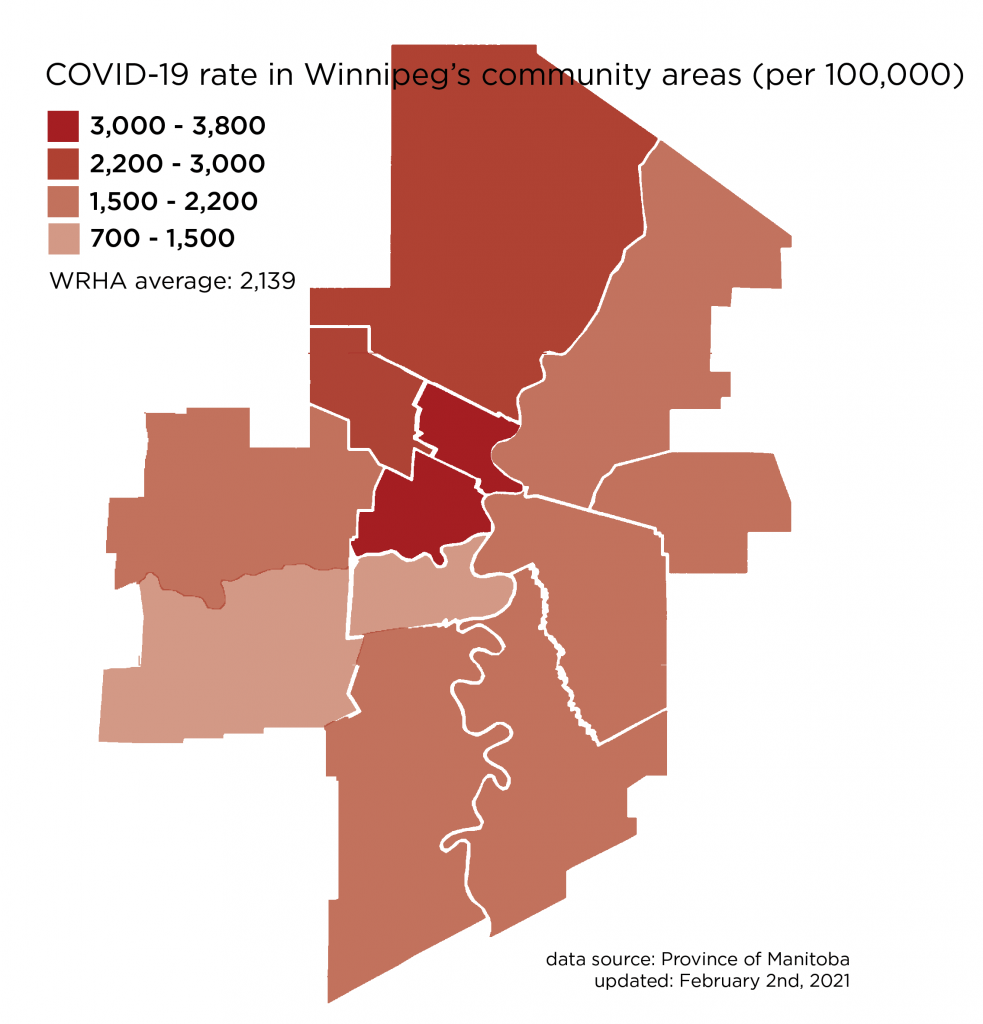

Here in Winnipeg, Point Douglas and Downtown are the neighbourhoods with the highest rates of COVID-19 at 3,000-3,800 cases per 100,000 people; they are also the neighbourhoods with the highest rates of poverty – almost 30 percent in some neighbourhoods – and the highest proportion of Indigenous people.

In other words, the ongoing impacts of colonialism and of social and economic injustice shape vulnerability to COVID-19. Successfully fighting the pandemic and building a just recovery will require action to reduce poverty and to decolonize policies and practices that result in marginalization.

The 2020 State of the Inner City report showed that when the pandemic arrived in Manitoba last March, the ensuing shut-downs and physical distancing requirements had an immediate and life-threatening impact on people’s access to basic needs in Winnipeg’s inner city. Drop-ins, resources and services, and washrooms were suddenly unavailable as community-based organizations, community centres, and public libraries shut their doors. For those who rely on these spaces for shelter and warmth, for food, for phone and internet access, for hygiene and for community, the abrupt closures resulted in upheaval and crisis.

These unintended consequences of the emergency response to the pandemic highlight the marginalization caused by a decades-long lack of investment in the welfare state. Health guidelines that insisted we stay home laid bare the lack of good quality, low-cost housing, including social housing, for thousands of households in Manitoba. Rapid changes in health protocols and the isolation caused by physical distancing made it clear that communications and internet access are an essential need, not a luxury. The lack of paid sick days forced many essential workers, especially those in low-paid and precarious jobs, to keep working and risk their health (and the health of others around them). And the CERB’s provision of $2000 per worker per month, while desperately needed and an essential support for millions of Canadians, made Manitoba’s EIA rates (currently $795 per month for a single person) seem tragically low.

At the same time, the pandemic has highlighted the innovative and essential role that community-based organizations play in mitigating the day-to-day impacts of poverty for communities in Winnipeg’s inner city. Food banks, Indigenous organizations, women’s centres, youth-serving and neighbourhood organizations provide safe spaces for people to gather, as well as essential services and resources for everyday life. In our interviews with 30 leaders and front-line workers, we heard how they have found new ways to reach out and provide programming, resources and supports to the communities they serve. They told us their relationships of trust with the communities they serve have been instrumental in helping hard-to-reach residents during the pandemic.

As vaccine distribution ramps up and we can begin to hope for an end to the pandemic, we cannot go back to “business as usual”, when “business as usual” means poverty, homelessness, and precarious employment for thousands of Manitobans.

To address the immediate task of dealing with COVID-19, the Province must work with community-based organizations. These organizations can act as a bridge between the Province and marginalized and vulnerable communities, sharing information about health guidelines and vaccines. This is especially important for Indigenous communities, which may lack trust in Western medicine, because as Niigaan Sinclair has noted “no one has been more experimented on than our communities”.

For the long term, we must reduce vulnerability by reducing social and economic marginalization. This means increasing the supply of social housing with rent subsidies and supports to keep people housed. It means providing a liveable income for all Manitobans that will cover basic needs including phone and internet access. It means ensuring that all workers have access to paid sick days, a decent minimum wage and childcare. And it means addressing racism and colonialism to ensure that Indigenous people are not disproportionately affected by pandemics and poverty.

These actions will reduce vulnerability to COVID-19, and get us all through the storm together.

Sarah Cooper is an assistant professor of City Planning at the University of Manitoba and a Research Associate at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives-Manitoba. She is a co-author of COVID-19: The Changing State of the Inner City – Strengthening Community at a Time of Isolation.

Maps: Justin Grift.