By Lynne Fernandez

Notwithstanding stable economic growth and consistently low unemployment, poverty remains a problem in Manitoba. In 2014, 11 per cent of Manitobans lived in low income. That’s down from 11.8 per cent in 2011, however child poverty continues to be stubbornly high, with the 2014 rate at 16.2 per cent.

The living wage is one of the most powerful tools available to address this troubling state of poverty amid plenty in Manitoba. It allows us to get serious about reducing child poverty and ensures that families who are working hard get what they deserve — a fair shake and a life that’s about more than a constant struggle to get by.

A living wage is not the same as the minimum wage, the latter being the legal minimum all employers must pay. The living wage sets a higher standard — it reflects what earners in a family need to bring home, based on the actual costs of living in a specific community. The living wage is a call to private and public sector employers to pay wages to both direct and contract employees sufficient to provide the basics to families with children.

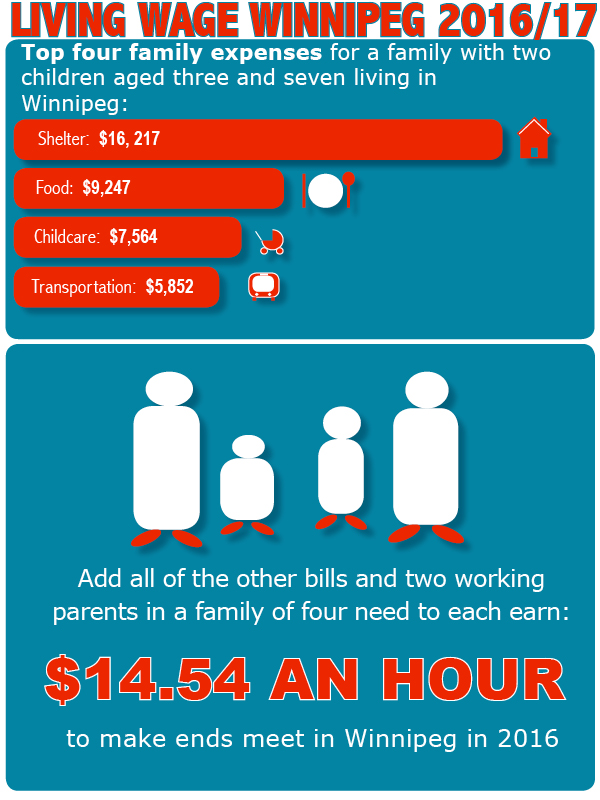

In 2016/17, a two-parent/two-child family living wage in Winnipeg is $14.54/hour; in Brandon $14.55; and in Thompson, $15.28.

The method for calculating the living wage is:

Annual Family Expenses = Living Wage + Government Transfers – EI, CPP, Income Tax

The following details show expenses for a two-parent/two-child family living in Winnipeg:

Food: $ 770.63

Clothing/footwear: $ 160.93

Shelter: $1351.46

Transportation: $487.74

Child care: $630.35

Private health insurance: $147.65

Parent’s education: $129.17

Contingency fund: $169.63

Household expenses: $702.39

This is a pretty bare-bones budget for a family of four. The living wage does not cover:

Credit card, loan, or other debt/interest payments;

Saving for retirement;

Owning a home;

Savings for children’s future education;

Anything beyond minimal recreation, entertainment, or holiday costs;

Costs of caring for a disabled, seriously ill, or elderly family member;

Much of a cushion for emergencies or tough times.

The 2016-17 update reveals two noteworthy developments. The first one is how much difference government policy can make in families’ lives: the new, non-taxable Canada Child Benefit, which replaced the old system of federal child benefits as of July 1, 2016, is a lot more generous for families with income under $100,000. The difference is so significant that even though this benefit started in July and was avail¬able for only six months of 2016, it boosts the family income enough to more than offset the increase in the cost of living. For example, our Winnipeg family receives $810.52/month.

The second development is the increase in housing costs. In Winnipeg housing went up almost 25 per cent (since 2013) for a two-parent/two-child family; in Brandon, 37 per cent; and in Thompson, housing increased by 39 per cent. None of these families qualify for the provincial Rent Assist program.

Despite the known benefits to providing families with adequate income, such as improvements in health, educational outcomes and overall wellbeing, critics will insist that a living wage is not necessary due to myths surrounding the impacts of increases to the minimum wage such as the assertion that it is mainly teenagers who earn minimum wage.

The number of workers in Manitoba who work for only minimum wage (set to increase to $11.15/hour) is increasing. Economist Armine Yalnizyan’s study on the minimum wage found that the percentage increased from 4.8 per cent to 6.8 per cent between 2006 and 2016. The percentage of Manitoba minimum wage workers employed by companies with more than 500 employees is 41 per cent, so not all these workers are working in small enterprises. Furthermore, Yalnizyan found that the rate of growth in incidence of minimum wage by age group is greatest in the 20-24 year-old category and second highest in the 25-54.

The other argument that inevitably arises is that increases in wages hurt the economy. Reliable studies refute that assertion, and as Yalnizyan explains, cost increases of many kinds (energy, for example) can cause struggling businesses to go under. But the increase in demand that comes from low-income workers being able to spend more will make the economy grow so it can create new jobs.

Research is also clear on another issue: wage increases improve worker performance and loyalty, thereby making living-wage employers more profitable.

Finally, the living wage is not just about employers — the labour market alone cannot solve all problems of poverty and social exclusion. Our standard of living is a combination of pay, income supports and accessible public services that reduce costs for families.

Direct government transfers can put money into the pockets of low-income families. The more generous these transfers are, the less a family requires in wages to achieve a decent quality of life – as demonstrated by the new Canada Child Benefit. However, most other government transfers and subsidies are reduced or eliminated once a family reaches an income level below the living wage.

Provincial and federal governments must review all low-income transfers and credits regularly to ensure that the amounts provided are keeping up with the actual expenses they are meant to defray (such as child care fees or rent) and that they are not clawed back at income levels that leave many families struggling with a bare-bones budget. When government transfers fail to keep up with the rising cost of living, the families who are the hardest hit are the ones headed by earners who are already marginalized and tend to do poorly in the labour market. The full report shows how single-parent families struggle even more.