By Molly McCracken

The federal government released its national poverty reduction strategy “Opportunities for All” last month. The plan has implications for the soon-to be released Manitoba poverty reduction plan. The federal and provincial governments must take serious action to bring down poverty rates in Canada. Incremental change will make little difference in the lives of those struggling in poverty.

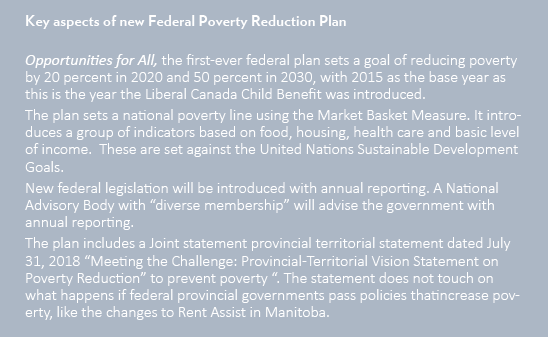

Poverty reduction plans are advocated by anti-poverty activists to set a clear path to ending poverty using a measured and accounted for government-wide coordinated approach. Please see the CCPA National blog on the federal plan for an overall analysis. The new federal plan assembles programs and commitments related to poverty in one document, but with no new money announced for implementation.

Manitoba’s poverty challenges require radical investment to end suffering and promote justice, particularly as it relates to Truth and Reconciliation.

The federal government has legislative and treaty responsibility to provide programs and services to Indigenous people on reserve, and in some cases off reserve. The disastrous consequences of unfulfilled federal obligations for adequate social services, housing, water & more hugely impact Manitoba. Manitoba’s on-reserve child poverty rate is a shocking 76% and 39% off reserve – the highest in the country (MacDonald and Wilson, 2016). Indigenous Manitobans on reserve are more likely to rely on federal welfare, called Income Assistance, 46.9%, compared to 33.6% average in Canada in 2017 (Clark, 2017). Federal Income Assistance rates are tied to provincial Employment and Income Assistance rates and woefully inadequate. Income transfers combined with economic development are key to bringing down poverty rates on and off reserve.

Community-led solutions to poverty are all around us, and it is our hope governments seriously listen to community in the creation of, and investment in, action plans to end poverty.

The View from Here: Manitobans call for a Renewed Poverty Reduction Plan includes 49 evidence-based community responses to poverty. This report was endorsed by 150 organizations, including Make Poverty History Manitoba (MPHM). MPHM worked with community groups to prioritize five areas for action based on The View from Here.

In the Manitoba 2016 election, all political parties campaigned on reducing poverty. To date the provincial government has done little and even reduced Rent Assist benefits and other programs that help to reduce poverty. The provincial poverty plan is a year and a half overdue from its planned release, in violation of the Poverty Reduction and Social Inclusion Act.

Manitoba should not ride on the coattails of the federal poverty reduction plan but invest real money to maximize impact. To this end, here’s what the federal plan means for the MPHM provincial priorities:

- Basic Needs for those living with low incomes

Welfare rates are sorely inadequate due to government decades-long holidays on inflationary increases. In Manitoba single adults on social assistance are 47% below the poverty line (Market Basket Measure, MBM) and people on disability are 33% below. Each year, assistance slips further and further below the cost of living. Another major problem with welfare for those who are able to get paid work: any earned revenue is clawed back 70% (after the first $200) and benefits such as dental and prescriptions are lost when one starts working. This makes it very hard to leave welfare.

In response to these problems MPHM announced its “Livable Basic Needs Benefit” campaign last February. MPHM proposes a provincial benefit set to the poverty line that tapers off with earned income, established outside of welfare.

MPHM’s provincial policy recommendation could be boosted with support from the federal government for implementation. Federal support for Make Poverty History Manitoba’s program could come in the form of an increase to Manitoba’s transfer payments to help bring basic needs benefits up to the poverty line. The 2018 CCPA Alternative Federal Budget calls on Ottawa to create a new $4 billion annual federal transfer payment to provinces/ territories tied to adequate social and disability benefit rates and positive outcomes in reducing poverty. Unfortunately this is not in the new federal plan.

2. Child care

The cornerstone of the federal government’s poverty reduction plan is the Canada Child Benefit (CCB). Campaign 2000 rightly pointed out that the Canada Child Benefit is not an anti-poverty program; families with children who receive this benefit are still below the poverty line. On top of this, CCB transfers money to parents but there is a terrible lack of quality affordable childcare. Manitoba is 10th out of the 11 provinces and territories with child care for only 31% of children according to Child Care Deserts in Canada. Manitoba’s wait list grew from 12,000 in 2016 to 15,487 children waiting for licensed childcare as of February 2018.

Canada’s economic productivity would increase if those unable to work for pay due to lack of childcare were able to join the workforce said Stephen Poloz, head of the Bank of Canada. The federal government must work with provinces and territories to create a universal publicly accessible child care system for all ASAP. Families require child care to earn money or get an education. And it’s important for child development and school readiness.

- Minimum wage

Much of the federal government’s efforts are on the “deserving poor”- families with children and seniors. But most of the poor are not those on assistance, but working poor according to CCPA’s Alternative Federal Budget. There is nothing in the federal plan about increasing the federal minimum wage to a living wage, adopting a federal government living wage policy or encouraging provinces to increase their minimum wages to $15 or a living wage. These actions would lead by example on the importance of paying a fair wage and put pressure on provinces to do the same.

- Mental Health and Addictions

People can find themselves struggling with poverty due to mental health concerns or addictions. Poverty is extremely stressful and can exacerbate these as well. High meth use in Manitoba is impacting crime rates (see “Meth is a Symptom, Poverty is the Crisis”. )To combat the negative impacts of meth use, government poverty plans must deal with the root causes of addictions and mental health concerns via comprehensive poverty reduction plans including social housing and inadequate social assistance rates. A lack of treatment facilities and no cost community supports are only exacerbating the crisis. MPHM recommends an increase in provincial mental health spending by 40 percent over three years. Additional federal funding for the opioid crisis will help, but should be no substitute for provincial investments.

- Social Housing

The Right to Housing Coalition and Make Poverty History Manitoba have long called on the province and the federal government to each commit to building hundreds of units of social housing per year. The National Housing Strategy launched last November provides $40 billion over 10 years to provinces to reduce core housing need. After decades of neglect, the new federal plan is a promising step, but much more is needed. The Manitoba government has not committed to building any new social housing since elected in 2016, and has sold off some of its stock to the private market. Two years after beginning consultations, we are still waiting on the release of the provincial housing strategy.

Manitoba should match federal funding in order to maximize impact. Housing is the cornerstone of poverty reduction. Those in quality affordable housing, in study after study, can escape poverty and improve health and educational outcomes. Manitoba cannot afford to skimp on social housing investment.

The National Housing Benefit will be a rent supplement to those in need, with a planned implementation date of 2020. Under development by the federal and provincial governments, the Benefit will look different in each province. The federal government has stated the new National Housing Benefit is not meant to replace existing rent subsidies like Rent Assist, but to meet the “unique needs” of Canadians. With expiring operating agreements and high and rising rental rates, Rent Assist is not going far enough to bring Manitoba renters out of core housing need. The National Housing Benefit should be designed to close the affordability gap for those in greatest need and those who are most vulnerable.

The five MPHM priority areas are part of the puzzle of solving poverty in our province and country. The federal and provincial poverty plans rely on each other to truly reduce poverty.

New investments in Manitoba will be needed to do this and not rely only on the National Housing Strategy and other federal programs. MPHM and its supporters are looking for a solid plan in Manitoba to substantially bring down poverty rates by targeted dates with strong accountability mechanisms.

MBM: measure of low income based on the cost of a specific basket of goods and services representing a modest, basic standard of living developed by Employment and Social Development Canada

LIM AT: household low income if its after-tax income is less than half of the median after-tax income of all households in Canada.

Sources: Statistics Canada, 2016 Census of Population, Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-400-X2016148.

Statistics Canada. Table 11-10-0018-01 After-tax low income status of tax filers and dependants based on Census Family Low Income Measure (CFLIM-AT), by family type and family type composition

Molly McCracken is the director of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives Manitoba and a member of the Steering Committee for Make Poverty History Manitoba.

By Lynne Fernandez

First published in the Winnipeg Sun September 8, 2018

In response to Jonathan Alward’s piece on municipal overspending, small business owners are not the only ones paying attention to municipal election platforms this fall. Those community members who participated in the 2018 Alternative Municipal Budget bring a very different perspective from the CFIB’s.

Mr. Alward complains of unsustainable spending growth, but provides few details. He refers to a CFIB report that found the main culprit to be municipal employees. Simply stating that labour costs take up 59% of any budget doesn’t really tell us anything. Workers are a crucial part of any municipality’s activities, so we should expect the wage bill to be substantial.

The real crux of the matter is an antipathy towards unionized workers. That workers should have benefits and make decent wages is a constant irritant for the CFIB, despite the fact that these wages are spent in CFIB member businesses. But if we take a closer look at where Winnipeg’s budget line is the highest, we’ll see that it is with the one group of workers business owners are reluctant to criticize: the police.

Between 2000 and 2016, the police budget increased from $115 million to $280 million – a 145% increase, compared to a 40% increase for public works. As the largest and fastest growing budget line in the Winnipeg’s operating budget, it may well be time for the Winnipeg to examine the cost of policing, especially when money for para-military equipment could be spent dealing with the root causes of crime. Departments that work to decrease social marginalization saw increases of only 13% in the same time period.

In the latest round of bargaining for CUPE 500 City of Winnipeg workers, increases were 0%. So when inflation is factored in (something the CFIB agrees should be), these workers’ salaries decreased 1.6%.

Wage increases in 2017 for other CUPE members working for Manitoba municipalities ranged between 1.0 and 2.5%, with the average being 1.89% – close to Manitoba’s 1.6% rate of inflation for 2017.

It is true that many cities in Western Canada do not have a business tax per se, but this is compensated for with higher rates on non-residential property taxes. When the business tax as a category was eliminated in Calgary and Edmonton, the non-residential commercial property tax was increased to ensure no loss in revenue. Businesses pay a similar total amount of tax in those cities as they do in Winnipeg. Furthermore, Winnipeg’s business tax has decreased every year from 9.75% in 2002 to 5.14% in 2018. A 2016 KPMG report found that Winnipeg had the lowest business costs of a sample of major North American cities.

The Alternative Municipal Budget agrees that budgets have to be sustainable, but we are referring to the need to deal with climate change and environmental degradation. These are the most pressing problems of our day and they require a heroical response that all sectors of society, including business, must be part of.

For example, we recommend implementing Mobility Pricing which would shift the unsustainable cost of road maintenance to drivers and investing in public transportation so that commuters have a viable, affordable option to single-occupancy vehicle use. Doing so would also lower greenhouse gases.

The CFIB does not consider the $1.4 billion that is needed to upgrade Winnipeg’s North End Water Pollution Control Centre, the lack of an organic diversion program in Winnipeg, its outdated and inadequate transit system, or offer any solutions for the infrastructure deficits all municipalities face.

It is not clear how Winnipeg will deal with a $6.9 billion infrastructure deficit when its yearly capital budget hovers around $430 million. The sixteen-year tax freeze imposed on Winnipeg by previous administrations made it impossible to borrow the money required to keep up with repairs.

Winnipeg has the lowest property taxes of Canada’s major cities. Between 1999 and 2017 property taxes increased 77% in Calgary, 84% in Edmonton, 63% in Vancouver, and 73%. In Winnipeg they increased 11%. Now compare the infrastructure in those cities with Winnipeg’s.

Even if we had kept up with inflation and population growth, Winnipeg couldn’t have maintained the status quo. Aging infrastructure must be kept in good repair, a monumental task given that developers, likely members of the CFIB, continually push for new infrastructure to accommodate urban sprawl.

Finally, does Mr. Alward advocate against CFIB members when they increase prices to cover their costs? The insurance sector warned of the effects of climate change as early as 1973, and continues evolving its business model, including increasing rates, to adapt to the changes. The Fort McMurray fire cost the industry between $5 billion and $9 billion, a cost passed on to property owners and businesses.

If the CFIB thinks that any municipality can prepare for climate change – including the disproportionate impact it will have on the poor, and deal with ageing infrastructure – all without somehow increasing revenues, it needs to get a reality check from those CFIB members who understand the new world we find ourselves in.

First published on CBC online July 8th, 2018

A Ferrari cruises down Portage Avenue past people lining the streets on lawn chairs on Sunday evening in Winnipeg. The $250,000 car purrs along the road, a symbol of incredible wealth.

Meanwhile, other Winnipeggers struggle to find bus fare to use our underfunded transit system.

The wealth of upper-income earners compared to the rest of is growing in Manitoba and Canada. When a segment of people drives way ahead, many others are left behind. But this is not inevitable; there are public policy remedies.

The top 10 per cent of earners are wealthier than ever – 44 per cent more so in Manitoba in 2014 than in 1976, according to a new study based on Statistics Canada data.

Last month the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives – Manitoba released Manitoba Inequality Update: Low income families left behind by Ian Hudson and Benita Cohen, which studies income for families with children and finds the majority of market gains in the past several decades have gone to the top earners.

While this might be good for the wealthy who like expensive cars, the data finds a growing gap between the rich and the rest of us. Market income is income from employment earnings, investment income but not government income. Economists use market income as a measure of inequality. The study finds lower-income people’s made more market income in the 1970s than in 2014. So this means low income people’s ability to earn money has been reduced over the past 30 years.

In 2014 the bottom 10 per cent earned 11 per cent less than in 1976 and the next lowest 20 per cent were also worse off. The middle deciles saw moderate gains.

Returning to the cruise-night analogy, this means 20 per cent of Manitoban families are standing still by the side of the road — the working and middle class are walking along the sidewalk and the wealthiest 10 per cent of families are speeding away at an accelerated rate.

Our economy and society are losing out as a result. Those at lower levels of income cannot realize their full potential. Being from a lower income household impacts social mobility: children from low-income families are less likely to graduate high school on time and go on to post-secondary education. This, coupled with the rise in precarious, part-time work, results in stagnant wages for young people.

Recent policy changes in Manitoba will make it harder for low-income and working-class students to get ahead. The Manitoba government recently allowed post-secondary institutions to increase tuition by five per cent annually, plus the rate of inflation. Tuition could double in the next decade and along with this, the hope of social mobility for those with lower incomes is squashed.

But with more progressive public policy, this need not be the case.

A recent Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives Manitoba study, Rising Tuition: Impacts for Access and Career Choice by Jesse Hajer and Zac Saltis, compared graduation rates from Organization for Economic Co-operative Development (OECD) countries. They find that increasing tuition brings down enrolment for low income students. Student loan programs do not increase enrolment from low-income students.

But countries with needs-based grant programs have increased post-secondary enrolment among low-income students.

At recent graduations across the province, families and friends witnessed the thrill of having a new degree in hand.

Imagine how different our province would be if everyone who wanted to go on to post-secondary education or training had the chance to do so without being burdened by student debt.

The human and economic potential if everyone had post-secondary education is significant: higher productivity, a stimulated economy and unleashed human talent.

Government has an important role to play to mitigate the huge disparities created by market inequality. Hudson and Cohen found that once government taxes and transfers are considered, the average income of bottom 10 per cent of Manitoban families with children increased from $4,500 to $23,000.

While this is an improvement, it is still below the poverty line of $28,000 for couple with children and $24,500 for single parents as measured by the Low Income Cut-Off After Tax measure, which Statistics Canada defines as the “threshold below which a family will likely devote a larger share of its income to food, shelter and clothing than average”). This is hardly enough to survive day to day. It is virtually impossible to go back to school for better education and training.

Rising inequality is not inevitable. Those who were around between 1940 – 1980 will remember we didn’t have this big a gap between the wealthy and lower income people. This was due to progressive income tax transfers and strong public services to the poor and middle class.

Government took action to increase incomes of working people by allowing for unionization. Other important measures that would help are a minimum wage set to a living wage of $15/ hour, improvements to Employment Insurance and liveable basic needs benefits for those on assistance.

But recent changes in Manitoba will increase inequality, not alleviate it. Bill 7 – the proposed Labour Relations Amendments Act – makes it more difficult for workers to unionize in Manitoba. The Carbon Tax credit does little to help low-income people, returning only 20 per cent of the cost of this tax to those below the poverty line, according to new analysis by Harvey Stevens published by CCPA Manitoba.

But this need not be the case. We need truly progressive public policy and redistribution of resources so that those who drive Ferraris pay bit more in taxes and those of us along the side of the road can at least get on the electric bus.

By Molly McCracken, Director CCPA-MB

By Lynne Fernandez,

Winnipeg cannot control broader macro pressures such as climate change or a stagnant global economy, but it can prepare for the changes that are coming. It can meet climate change with policy to mitigate damage, slow the rate of change, and build resilience. It can stimulate and grow the local economy while making sure that marginalized citizens are included. It can put the brakes on wrong-headed practices like urban sprawl or over-spending on policing, while redirecting resources to deal with the root causes of crime and our infrastructure deficit, and smooth out the inequalities that keep our city from realizing its full potential.

The 2018 Alternative Municipal Budget (AMB) is a community response that dares to imagine a greener and more equitable Winnipeg.

By Ian Hudson and Benita Cohen,

A decade ago the CCPA-MB released the Stuck in Neutral report on inequality in Manitoba. Although inequality was less pronounced in Manitoba than it was in other provinces, earnings for the poorest 40% of families were either no higher or actually lower in the early 2000s than they were in the late 1970s, despite families working longer hours. Since that report was released the global economy suffered through a massive economic crisis in 2008, oil prices spiked and collapsed, and provincial governments have come and gone. It seemed a reasonable time to update the study to see if the trends uncovered in the early years of the new millennium still hold.

Follow us!