Looking for information about housing in Winnipeg? Look no further – here are the updated facts and statistics about housing in Winnipeg and Manitoba. (The previous page is here).

References are available at the bottom of the page, in case you are looking for more details.

Core Housing Need

Definition of Core Housing Need

“Acceptable housing is defined as adequate and suitable shelter that can be obtained without spending 30 per cent or more of before-tax household income. Adequate shelter is housing that is not in need of major repair. Suitable shelter is housing that is not crowded, meaning that it has sufficient bedrooms for the size and make-up of the occupying household. The subset of households classified as living in unacceptable housing and unable to access acceptable housing is considered to be in core housing need.”(1)

Core Housing Need

In 2006: (2)

- 11.3 % of all MB households lived in core housing need (46,900 people)

- 24.0 % of MB renter households lived in core housing need (28,800 people)

- 6.2 % of MB owner households lived in core housing need (18,100 people)

- 22.3 % of those who immigrated to Canada between 2001 and 2006 lived in core housing need in Manitoba (1,600 people)

In 2006: (3)

- 37.3 % of Winnipeg tenant-occupied households spent over 30% of their income on housing.

- 11.6 % of Winnipeg owner-occupied households spend over 30% of their income on housing.

Renting in Manitoba

Current Vacancy Rates

In October, 2011, the vacancy rate was (4)

- 1.0 % in Manitoba, the lowest vacancy rate in the provinces

- 1.1 % in Winnipeg, the second-lowest among all CMAs in Canada

- 0.0 % in Thompson

- 0.6 % in Brandon

- 1.0 % in Portage la Prairie

Source: (5)

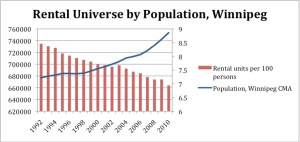

Winnipeg’s Rental Universe

(This data only applies to apartment buildings with three or more units)

The rental universe in Winnipeg (6)

- has declined in 15 of the past 18 years.

- Lost 835 rental units, of which at least 450 units were permanently removed from the rental universe, between October 2009 and October 2010 (leaving 52,319 units).

Since 1992, Winnipeg’s rental universe has declined from 57,279 units to 52,319 in 2010, a decline of about 9 percent (7). At the same time, the population of Winnipeg has increased from 677,000 to 753,600, an increase of about 11 percent (8).

- The result is a drop in the number of rental units per 100 people from 8.5 units to 6.9.

Rents

In October 2011, the average rent was (9)

- 744 $ in Manitoba (compared with 711 $ in October 2010)

- 754 $ in Winnipeg (compared with 719 $ in October 2010)

- 683 $ in Thompson (compared with 668 $ in April 2010)

In 2011, the Median Market Rent in Manitoba was: (10)

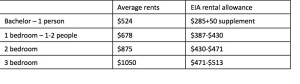

Affordability of Average Rents in Winnipeg (11 and 12)

EIA and Rent in Winnipeg (13 and 14)

Demographics

Migration

In 2010, 15,803 international migrants came to Manitoba, and 12,340 immigrants moved to Winnipeg. (15)

The population of Manitoba increased by 15,800 people from 2009-2010 (from 1,219,600 to 1,235,400). (16)

The population of Winnipeg increased by 9,700 people from 2009-2010 (from 674,400 to 684,100). (17)

Social Housing

Manitoba Housing “owns the Province’s housing portfolio and provides subsidies to approximately 34,900 households under various housing programs. Within the portfolio, Manitoba Housing owns 17,600 units of which 13,100 units are directly managed by Manitoba Housing and another 4,500 units are operated by non- profit/cooperative sponsor groups or property management agencies. Manitoba Housing also provides subsidy and support to approximately 17,300 households (including 4,700 personal care home beds) operated by cooperatives, Urban Native and private non-profit groups.” (18)

National Social Housing Construction

In 1993, the federal government withdrew from housing. Until then, about 10 percent of the housing built each year in Canada was affordable to lower income households; since then it has been less than one percent.

Sources

(1) CMHC 2011, Canadian Housing Observer.

(2) CMHC 2006, Canadian Housing Observer. Also offers data on types of family, Aboriginal status, and period of immigration

(3) City of Winnipeg 2006. 2006 Census Data – City of Winnipeg.

(4) CMHC 2011, Fall. Rental Market Report: Manitoba Highlights.

(5) CMHC 2011, Fall. Rental Market Report: Winnipeg CMA.

(6) CMHC 2011. Rental Market Report: Manitoba Highlights.

(7) CMHC 2011. Personal communication from Dianne Himbeault, CMHC.

(8) City of Winnipeg. 2011. Population of Winnipeg.

(9) CMHC 2011, Fall. Rental Market Report: Manitoba Highlights.

(10) Government of Manitoba, date unknown. Housing Income Limits and Median Market Rent

(11) City of Winnipeg 2006. 2006 Census Data – City of Winnipeg.

(12) CMHC 2011, Fall. Rental Market Report: Winnipeg CMA.

(13) CMHC 2011, Fall. Rental Market Report: Winnipeg CMA.

(14) Employment and Income Assistance Facts. Government of Manitoba.

(15) Government of Manitoba. 2011. News and Resources.

(16) City of Winnipeg. 2011, May 1. Population of Winnipeg.

(17) City of Winnipeg. 2011, May 1. Population of Winnipeg.

(18) Manitoba Housing and Community Development. 2010. Annual Report 2009-2010.

(19) CMHC. 2011. CHS – Public Funds and National Housing Act (Social Housing).

By Errol Black

During the recent discussions on changes to the formula for federal contributions to health care spending, Saskatchewan Premier Brad Wall signalled that his province (which is flush with resource revenues from potash and oil) could live with the new arrangements. At the same time, however, Wall suggested that a Health Care Innovation Fund be created to help fund significant innovations in healthcare in the provinces. A working group was subsequently established by the premiers to work on healthcare innovation. The working group is co-chaired by Wall and Premier Robert Ghiz, Prince Edward Island, and includes health ministers from provinces and territories.

Prime Minister Harper rejected Wall’s proposal to create an “extra fund” but said he would be interested in getting fresh proposals from the premiers on how to sustain Canada’s health-care system.

As it turns out, Wall and his Saskatchewan government are already moving forward with one innovation that could have a profound impact on heatlhcare delivery in that province and perhaps others. It is, moreover, precisely the sort of innovation that would appeal to Stephen Harper.

In recent years, the Wall government has been experimenting with the application of lean-management principles to in the healthcare sector. Early applications in the Five Hills Health Region in Moose Jaw apparently produced some promising results. So promising in fact that the CEO of the Five Hills Health Region, Dan Florizone, was recruited to pave the way for the introduction of lean-management principles and practices across the province to include “all of its 43,000 workers and managers.”

The plan will proceed in two stages. Phase 1 involves “strategy deployment” – or the establishment of priorities. Phase 2 involves getting all healthcare components – agencies, hospitals, councils, etc. – “thinking like a synchronized lean machine. Indentify waste, test a possible fix, evaluate the outcome and repeat. The cycle can, and should, go on forever.” The claim is also made that workers have bought into the process and are contributing input to design of the new Moose Jaw Union hospital and a new Children’s Hospital in Saskatoon.

An American consulting firm, John Black and Associates, is to provide the expertise required to transform the culture and shape the system to the lean philosophy.

All of this has its origins in the example of the lean production/ lean management methods of Toyota (much of which is reminscent of the practices of scientific management from the late 19th and early decades of the 20th centuries). The big push for the adoption of lean management in North America comes, apparently, from the Kaizen Institute, which bills itself as a “Global Leader in Continuous Improvement Strategy”.

It does indeed seem that Saskatchewan is on the “cutting edge” of innovations in healthcare delivery, although we suspect that this approach will have more to do with cutting costs and deskilling hospital workers than it does with enhancing jobs and improving healthcare services. This is a particular concern when American firms are recruited to lead the way in transforming the culture and shaping the system to the lean-management philosophy.

We need to know:

- how workers and their unions feel about the approach to lean-management in Saskatchewan;

- if similar approaches are underway or contemplated in other jurisdictions in Canada;

- and, if the federal government has signalled that this approach is approved as an example of the sorts of private-public-partnerships they would support.

This is potentially the start of a fundamental change in the way our healthcare services are delivered, and we will be keeping a close eye on how things progress in Saskatchewan.

by Ben Gillies

For many Winnipeggers, the news from Main Street last week was long overdue. On Wednesday, city council voted in favour of a preliminary design to finally widen Kenaston Boulevard to six lanes of traffic between Ness and Taylor avenues. As noted in the Winnipeg Free Press, the plan is to expand the roadway on the west side by acquiring land from Kapyong Barracks, and on the east by demolishing about 50 homes. Admittedly, actual construction of the proposed alignment may not move forward for several years, since the desired Kapyong Barracks land is currently at the centre of a federal court case between Ottawa and a number of First Nations groups. Nevertheless, the vote on a project meant to improve the state of almost permanent gridlock along Route 90 will likely be welcomed as a decision that, according to conventional practice, should have been made a long ago. As Winnipeg’s public works director Brad Sacher notes, current road standards suggest a street be widened to six lanes when traffic counts are above 35,000 vehicles per day, while volumes along the boulevard have been upwards of 50,000 cars and trucks per day for decades, and between 60,000 and 70,000 vehicles daily in recent years.

The decision to invest millions of dollars in this project was made based on the seemingly commonsense belief that expanding the number of lanes along a major artery is the best method of alleviating traffic congestion. Interestingly, however, new research suggests this long-held assumption may not in fact be true. Last year, economists at the University of Toronto analyzed reams of travel and roadway construction data from across the United States going back two decades, and they discovered that “vehicle-kilometres traveled […] increase proportionately to roadway lane kilometres”. Or, to be more concise, “roads cause traffic”.

The basis for this decidedly counterintuitive conclusion is the three-pronged ‘fundamental law of highway congestion’: “people drive more when the stock of roads in their city increases; commercial driving and trucking increases with a city’s stock of roads; [and] people migrate to cities which are relatively well provided with roads”. Basically, drivers use their vehicles more frequently as the road network expands. As was discovered in the American statistics, when more lanes or roads became available there was a proportional rise in the amount of driving done by motorists, meaning the “increased provision of interstate highways and major urban roads is unlikely to relieve congestion of these roads”. Moreover, the economists found building larger public transit systems is by itself an equally insufficient solution. Because there are always drivers waiting for extra space on the road, a former motorist taking the bus only provides the opportunity for another to fill their place on the street, with no change in the overall amount of traffic.

While there was little media fanfare over this research when it came out, the economists’ findings are worthy of note, as they throw the North American approach to reducing gridlock on its head. For years city planners have expanded roadways (and to a lesser extent, public transit systems) in an attempt to ease the pressure on an increasingly overcrowded transportation network, yet the empirical evidence indicates any relief was only temporary. Unfortunately, on the whole cities appear to have been left worse off by such investment, as congestion quickly returned but municipalities were permanently shouldered with the burden of maintaining more and more expensive infrastructure.

Of course, it is worth acknowledging that, despite the real-world findings of the Toronto economists, theoretically there is a point where road construction will alleviate congestion. If the City of Winnipeg chose to expand Kenaston Boulevard to, say, 100 lanes of traffic, it would obviously never be backed up. The problem, however, is that adding enough lanes to adequately mitigate gridlock would often be unrealistic in the confined area of a city, aesthetically unpleasant, and almost assuredly not financially feasible. This last fact is likely the most critical in Winnipeg, as the city cannot even afford the streets it has now. According to the Winnipeg Sun, about one-fifth of our roads have been designated “poor” by the public works department—the worst rating the agency gives—and are in such dreadful condition they have essentially been written off. Due to a lack of funding, the department has no plans to repair most of these streets in the next fifteen to twenty years, and is struggling just to ensure no more roads fall into such a state of disrepair. Overall, Manitoba’s capital has an infrastructure deficit—the difference between the amount of money the city government has and what it needs to maintain all its assets—exceeding $3.9 billion, and the Winnipeg Public Service projects the gap will grow to over $7.4 billion in the next decade.

The Route 90 proposal is certainly not the only arterial widening project on the municipal government’s agenda. In fact, in its latest planning document, the 2011 Transportation Master Plan, the most well-developed chapter pertains to street construction. Unlike the sections on transit, sustainable transportation, and the like, which offer some fantastic qualitative ideals but only sketchy quantitative projections, the street improvements are fully priced out in short-, medium-, and long-term plans. If the data is to be believed, however, such an adherence to road expansion will be decidedly ineffective in easing the pressure on our transportation network in any sort of financially sustainable way. As such, officials should consider a more holistic approach to alleviating gridlock that, unlike enlarging highways and roads, which only creates new demand, promotes a more responsible, moderated use of our transportation infrastructure.

Like almost all Canadians, one of the central assumptions Winnipeggers hold about our transportation network is that it is a public good; that is, the use of a road by one individual does not impede the ability of others to use the same road. Unfortunately, while this is true if there are only a few cars on the street, when we reach the level of traffic congestion seen on this continent, roadways take on traits comparable to those of hydro or water systems. Just as only so much electricity or water can flow through a power line or pipe at any one time, there is only so much room available for cars on the street, leaving the potential for similarly negative results if user demand surpasses available supply. When there is an overloaded demand for electricity, the system fails and no power can pass through the hydro line. Likewise, when too many motorists attempt to simultaneously use the limited space on a road, a traffic jam is created and the ability of any one driver to travel easily around the city is hugely impeded. The major difference between the two is that while hydro blackouts are a rarity and often even make headlines when they do happen, we have come to accept ‘transportation blackouts’ of major roadways as an inevitable and daily occurrence.

To encourage citizens to use scarce road space responsibly, just as they would electricity or water, the University of Toronto economists suggest planners and citizens ought to consider treating the transportation system in a manner not unlike home utilities, where financing is provided for the initial infrastructure construction and then consumers are charged a fee relative to how much they use the service. This would actually be easier than ever in the digital age, as all vehicles could be equipped with some type of GPS device that electronically tracks when and where citizens have driven, with drivers mailed a monthly bill. This type of road pricing is already common in other parts of the world, and even some US states including Oregon and Texas have trialed similar initiatives. Going beyond a flat fee per mile, these hi-tech systems take into account every choice a motorist makes and provide positive and negative inducements to smooth out traffic flow. Motorists are rewarded for choosing a longer but less clogged route, for example, or for driving during off-peak hours. In this regard, a road-pricing plan is actually superior to how governments currently charge motorists for driving—through the gas tax. While the fee at the pumps is a blanket cost for drivers, having the same effect on a major city street at rush hour as an abandoned country road at midnight, fee-per-mile programs are designed to actively moderate traffic through the use of incentives meant to alter how and when someone chooses to travel.

Admittedly, many people may question the notion of charging motorists to drive. Yet, done properly, designing a Winnipeg road-pricing plan could result in the establishment of a more equitable method of financing our transportation system, and lead to a more pleasant travel experience for commuters. Currently, Winnipeggers who choose to, for example, walk or telecommute to work still fund street maintenance and construction through their tax dollars as much as car commuters, even though they use the roads far less frequently. Meanwhile, Manitobans who live in lower-tax municipalities just outside the capital city’s limits but work inside the perimeter make use of city roads without paying for their upkeep. A system of road pricing would help mitigate both of these inequities, by charging all citizens who use the valuable transportation infrastructure on a regular basis more for that privilege than those who do not.

The money raised through the road pricing system could be dedicated to maintaining our stock of roads—which would certainly lead to an improvement over today’s often bumpy ride to work. Alternatively, there would be great value in putting a healthy portion of the funds towards upgrading the Winnipeg Public Transit system by adding more buses, lowering fares, building more rapid transit lines, increasing park and ride accessibility, and providing more bike lanes. Making public transit a more attractive alternative to driving is the perfect complement to the road-pricing scheme, and the resulting increase in ridership would lead to an overall improvement in Winnipeg’s commuter experience.

While those who chose the public option would be saving money on gas, parking, and insurance, taking these former drivers off the road would be equally advantageous to those who still got behind the wheel everyday. The most obvious benefit to the remaining motorists is that there would be less congestion, reducing the amount of time they must spend on their daily drive to work. Beyond that, there would also be the potential to scale back the total amount of road infrastructure in Winnipeg—or at very least mitigate the seeming need to build more—which reduces the financial pressure on the city and its taxpayers to maintain as many assets, and leaves the public works department in a better position to adequately look after what remains. Furthermore, studies indicate putting more people on one bus instead of in multiple cars could potentially reduce the pummeling our roads suffer every day, which makes for a more pleasant drive and lowers the cost of upkeep. Lastly, by increasing the proportion of vehicles on the road driven by professionals, who tend to have lower crash rates, and reducing the number of vehicles on the road in absolute terms, it has been shown boosting transit ridership among commuters would diminish the risk of traffic accidents and injuries to drivers, pedestrians, and passengers alike.

Today, approximately 50% of the space taken up in a typical North American city is for the roads, highways, parking lots, and the other infrastructure necessary to accommodate private automobiles. Adding extra lanes only spreads the urban area further, making it even less practical for residents to choose a mode of transportation other than a car. This leads to more vehicles on the roads, which then require places to park, eating up more space and pushing buildings further apart again. While each addition may be small—one extra lane here, a parking lot there—over time the result is an urban landscape that actively discourages walking, cycling, and taking public transit because distances between any two points are far too great. Congestion is maintained or even exacerbated, while taxpayers are forced to pay for evermore infrastructure. Road pricing reverses this vicious cycle, employing a market-based approach designed to cut automobile traffic and boost transit ridership that charges drivers based on their personal use rather than through a general tax on income—which ought to appeal to Winnipeggers on both the political left and right.

It is time the citizens and political leaders of Manitoba’s capital took a critical look at how we understand and design our transportation network. At very least, it is necessary to acknowledge the evidence illustrating the inadequacy of road and transit expansion as the sole or even primary gridlock alleviation strategies, and explore new demand-side mitigation measures reflecting this reality. Implementing the road pricing recommendations outlined in this document may initially strike people as unpalatable, but with the country’s worst per capita infrastructure deficit, citizens need to examine the potential benefits of moving beyond just boosting roadway capacity when it comes to dealing with our traffic woes.

More broadly, while we on the prairies may be in a worse bind than our counterparts in other jurisdictions, Canadians from coast to coast ought to consider the value of a new approach to transportation problems. A 2007 survey by the Federation of Canadian Municipalities found the great white north needs an additional $21.7 billion to maintain and upgrade existing transportation assets, and in the past few years this deficit has made headlines as bridges and other infrastructure has literally begun to crumble around us. Meanwhile, it was recently revealed Canadians experience some of the worst commute times in the developed world. Such a situation is unsatisfactory and unsustainable, and indicates we would be wise to adopt the pragmatic recognition that road space is a scarce and valuable commodity, and must be treated as such. Because unfortunately, when comes to gridlock, it is all too clear the conventional strategy of building more roads and hoping for the best is taking us nowhere fast.

Benjamin Gillies is a political economy graduate from the University of Manitoba. His research interests include urban development and energy policy.

By Lynne Fernandez

I was listening to the CBC Radio business reporter explaining what was happening at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. He was impressed by the number of billionaires who were present (I don’t remember how many, but it was a lot). The other thing he found noteworthy was that the growing gap seemed to be a popular topic of conversation. He reminded us that only a few years ago, concerns about the growing number of poor contrasted with an increasingly bloated über-rich class were only highlighted by the “radical” left.

The radical left. That’s a loaded term if there ever was one. Today, most consider a radical thought or person or movement as unreasonable, way out there – downright loony. The business reporter did not offer any sort of explanation of how the topic migrated from the loony left to being worthy of attention by a bunch of billionaires and their political apologists. It might have something to do with the left not being so radical after all — in the popular definition of “radical” — or it might have to do with the left truly being radical in the original meaning of the word.

by Shauna MacKinnon

We learn fairly early in life that when you apologize for something that you have done wrong, it is expected that your apology will be followed by a change in behaviour. The result of Prime Minister Harper’s meetings with First Nation Chiefs will tell us whether or not he has learnt this lesson.

In 2008, Prime Minister Stephen Harper publicly apologized for Canada’s role in the “aggressive assimilation” of Aboriginal children through the government-supported, church-run residential schools. The strategy was to separate Aboriginal children from their families, communities, languages and cultures, by placing them in institutions whose purpose was to “kill the Indian in the child”. The Harper apology was an admission that the idea was not only deeply flawed, but had caused a great deal of pain and damage for generations of Aboriginal families.

It was an important moment in Canada’s history, one that Aboriginal people had long waited for. Aboriginal leaders graciously accepted the apology, albeit some with a healthy dose of skepticism. The hope was that change would follow, and the Truth and Reconciliation Commission was seen to be a first step in the process of healing and moving forward. However, actions that have followed suggest the Harper government’s policy direction contradicts the spirit of the apology and moves us backward.

One such example is Bill C-10, the Crime Omnibus Bill.

On September 20, 2011, a few months after winning a majority election, Stephen Harper’s Justice Minister, Rob Nicholson, tabled Bill C-10, an omnibus bill titled the Safe Streets and Communities Act. The Bill combined nine separate bills that had failed to pass in previous sessions of parliament. The Canadian Civil Liberties Association (CCLA) says that Bill C-10 will “fundamentally change every component of Canada’s criminal justice system”.

There is also significant evidence to show that it will not accomplish what it intends. The CCLA states that “jail more often, for longer, with more lasting consequences – is a dangerous route that is unsupported by the social science evidence and has already failed in other countries.” Indeed, the research suggests that putting an individual in jail for longer will actually increase the likelihood of re-offending. It’s hard to see how this Bill will make streets and communities safer. What it will do is needlessly increase the number of people in prison, while producing skyrocketing costs and imposing unjust, unwise and even unconstitutional punishments.

While Bill C-10 does not explicitly target Aboriginal people, the implications for Aboriginal people cannot be ignored. Many argue that the Harper government policy is essentially creating a new form of residential school. As stated by Grand Chief Derek Nepinak of the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs (Winnipeg Free Press, Dec. 7, 2011), “Instead of investing in jails we need to invest in healing,”

It has long been understood that there is a strong association between severe poverty and crime. The government of Canada’s own website states that “Social and economic disadvantage has been found to be strongly associated with crime.”

The rate of poverty for Aboriginal people in Canada far exceeds the rate for non-Aboriginal people. Manitoba has among the highest Aboriginal populations in Canada, and the statistics here are staggering. The rate of Aboriginal poverty in 2006 was 29%, almost three times the overall poverty rate. Fully 37% of all Aboriginal people in Winnipeg are living in poverty — they make up approximately 10% of Winnipeg’s population yet constitute 25% of those living in poverty.

Aboriginal children under six years of age had a poverty rate (before tax LICO) of 56% compared with 19% for non-Aboriginal children. The median annual income for Aboriginal workers aged 15 and over in Manitoba was $15, 246 —63% of the median income of $24,194 of the overall population.

According to Census Canada 2006, the Aboriginal unemployment rate was 15.4% in Manitoba, almost three times the rate for the overall population. On reserve, the unemployment rate was 26% in 2006. Although they make up less than 13% of the work age population, Aboriginal people represent over 30% of the total unemployed in Manitoba.

These statistics are particularly troubling in Manitoba when we look at demographic trends. The Aboriginal population is young and growing at a faster rate than the non-Aboriginal population. In 2006, the median age of Manitobans was 37.8 years, compared with 23.9 for those who identified as Aboriginal.

Aboriginal people continue to be among those most disadvantaged, and while the majority of Aboriginal people excel in spite of the obstacles they face, they are extremely vulnerable by virtue of being so disadvantaged. This accounts for the fact that 18% of people in Canada’s jails are Aboriginal, despite being only 3% of the total population (Stats Canada, 2006 Census). In Manitoba, where the Aboriginal population is approaching 15%, 70% of those in custody are Aboriginal, according to the Manitoba Governments own data.

It is particularly concerning that the involvement of Aboriginal youth in street gangs has increased in Canada and especially in the Prairie provinces. It is estimated that “twenty two percent of known gang members in Canada are Aboriginal and that there are between 800-1000 active Aboriginal gang members in the Prairie provinces” (Totten, 2008). While the vast majority of Aboriginal young people do not join street gangs in spite of their vulnerability, those who do are drawn to them for many reasons rooted in the legacy of colonial policies, including residential schools.

The Harper apology did not wipe away the damage done by residential schools and colonization generally, and policies like Bill C-10 will only serve to perpetuate the damage. What is needed, in keeping with the residential school apology, is a commitment to a new policy direction aimed at supporting Aboriginal people in raising themselves out of poverty. This must include investment in the long-term healing of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal people through decolonization and cultural reclamation, together with increased and longer term investment in literacy, education and training, housing and job creation.

Shauna MacKinnon is the Director of the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives

By Errol Black

A 2011 OECD report on social justice in OECD countries ranks Canada, with a score of 7.26, in 9th place. The 31 countries were evaluated on the basis of six key measures: poverty prevention; access to education; labour market inclusion; social cohesion and non-discrimination; health; and intergenerational justice.

The top five countries and their scores are Iceland (8.73), Norway (8.31), Denmark (8.20), Sweden (8.18) and Finland (8.06). In contrast, our partners in the NAFTA, the United States and Mexico rank 27 and 30, respectively, with scores of 5.70 and 4.75.

When it comes to poverty prevention, however, Canada has a score of 7.00, which is just above the OECD average of 6.91, and good only for 18th place in the ranking.

While Canada’s ranking is still much better than the U.S. and Mexico (ranked 29th and 31st respectively, with scores of 3.85 and 2.11) the question that arises is: what accounts for the relatively poor ranking with respect to poverty prevention?

The measure for poverty prevention incorporates three variables, namely, poverty rates for the total population, children and seniors. Canada, with a poverty rate for seniors of 4.9 per cent ranks 4 of 31 on this variable (behind only the Netherlands, Czech Republic and Hungary with rates of 1.7, 3.6 and 4.7 per cent, respectively).

However, when it comes to the overall poverty rate and the poverty rate for children we have a different story. Canada’s overall rate of 12 per cent places us 21st in the ranking – but still ahead of the United States and Mexico at the very bottom with poverty rates of 17.3 and 21.0 per cent, respectively.

The child poverty rate for poverty in Canada is 14.8 per cent, placing us 23rd. Here again we continue to outrank the United States and Mexico with poverty rates of 21.6 per cent and 25.8 per cent. Unfortunately, we can take little comfort in this. On the contrary, the current situation in a rich country like Canada is scandalous.

In 1989, we pledged to eliminate child poverty. This didn’t happen. Instead we grew more tolerant of sustained levels of poverty, absolved corporations of virtually any responsibility for covering through their taxes the overheads of the general population and looked to private charities to take care of the homeless and the hungry, including increasing numbers of children.

We can’t blame this just on the federal government in Ottawa. It is also the responsibility of provincial governments, including NDP governments in Manitoba that have accepted a status quo dictated by neoliberal conceptions of the way the world works, and local governments that insist they are not responsible for the plight of the poor. And it is the responsibility of all the rest of us, who turn a blind eye to the plundering of the nation’s wealth by the rich and powerful at the expense of poor and needy.

How do we change this shameful legacy?

Errol Black is a member of the CCPA-MB board.

The full report is available here.

Le rapport complet est disponible ici.

by David Alper, Halimatou Ba, Mamadou Ka, and Bintou Sacko

Many obstacles confront newcomers in their efforts to integrate into Canadian society. Their search for employment is often frustrated by the failure to recognize their qualifications and education, and their lack of “Canadian” experience. Many immigrants arrive here with little knowledge of English. Finding adequate housing is also a challenge, especially given the large number of children in many newcomer families. Lack of access to suitable housing is perhaps the most daunting obstacle facing Manitoba’s francophone newcomers.

A research project conducted by the authors and funded by the Manitoba Research Alliance examined the specific housing concerns and circumstances of Winnipeg’s francophone newcomer community. The study considered the numerous studies demonstrating that access to decent, affordable housing is an important factor in the successful integration of newcomers into Canadian society. The housing crisis is severe in Winnipeg, with some 37% of tenant households facing core housing need, meaning they are paying more than 30% of their income on rent.

The study’s main goal was to examine the housing conditions of francophone newcomers in Winnipeg, its impact on their health, and their ideas of collective solutions to the housing crisis.

Some 85% of francophone newcomers now originate from Africa. These newcomers carry “triple” minority status, as immigrants, francophones and visible minorities, and their integration into Canadian society is hampered by discrimination.

Of the twelve families interviewed, seven were refugees from the Congo and Rwanda, and tended to have much larger families. The five other families were immigrants from Morocco, Guinea, Ivory Coast and Togo. Most refugees had been unemployed for over two years; those with jobs worked part-time or on call.

Participants’ housing experiences were varied. Most refugee families transited through government-funded housing facilities, such as Welcome Place, before finding their own housing. Immigrant families had to find their own accommodation upon arrival in Winnipeg. Most newcomers end up in inner-city neighbourhoods characterized by cheaper, run-down housing stock. One participant stated, “The window in the bedroom was broken and held together by scotch-tape…the heater in the children’s bedroom made a terrible racket… in the shower, there was a hole in the ceiling that leaked water from upstairs. The landlord promised to repair things, but hasn’t done anything”.

Families complained of the many obstacles they faced from landlords, including racist attitudes: “I once called and then went to look at an apartment in Windsor Park. When I got there, they saw that I was black and they told me the apartment was no longer available”.

As many newcomers have large families, overcrowding in apartments was a common problem: “Having four girls share the same bedroom, they all catch the same cold at the same time…”

Most families reported health problems related to their housing conditions, including stress, insomnia, headaches and allergies. These problems are in addition to many pre-existing health concerns arising from war-related trauma. “You encounter stress everywhere. When you first arrive here, there’s culture shock. Then you face all sorts of barriers and obstacles. There’s the language barrier. If you don’t speak English well, you can’t find a decent job. Then there’s all the prejudice arising from the fact that you are a visible minority. Even if you are just as good as the next guy, you always have to prove yourself. The stress is never-ending”.

Living in sub-standard housing leads to a general feeling of stress and frustration, especially when such a large part of household income goes towards rent, making it necessary to cut the food budget to the point where children go to school hungry. A number of respondents complained of vermin, or inadequate heating and ventilation systems that contributed to problems like asthma. “There were mice everywhere, and they were a constant source of fatigue”.

Parents also spoke of the demoralizing effects of being unable to adequately support their children, due to the high cost of rent. “Being unable to offer things to your child that all his friends have is upsetting to him. He becomes like a caged lion, furious all the time”.

When asked how they thought their situation could improve, participants saw an important role for government. They saw it as responsible for the housing crisis, but also holding the capacity to solve it. They believed that their difficulties in finding decent, affordable housing represented a formidable obstacle to their successful integration into Canadian society. They spoke of government action that would include “a short and long term housing policy …facilitating home ownership”, and also “building affordable housing… either housing cooperatives or low-cost housing”.

However, the Canadian government withdrew from the creation of social housing in 1993, contributing to the worsening of the housing crisis throughout the country. In fact, the Canadian government is the only G-8 country without a national housing strategy. The government’s attitude is in stark contrast to that of francophone newcomers from Africa, who come from cultures that value community and collective practices.

The participation of newcomers to movements fighting for social housing represents a source of hope for social change. With the increase in francophone immigration to Manitoba, new community resources and institutions have sprung up to help integrate these newcomers. However, civil society is incapable on its own to meet the challenge of finding decent, affordable housing for these newcomers. As with all low-income communities, comprehensive government programs must lead the way. The government is aggressively recruiting immigrants to settle in Manitoba; it is high time that it tackle the housing shortage head on so that these Manitobans can build decent lives.

David Alper, Halimatou Ba, and Mamadou Ka all teach at Université de Saint-Boniface, and Bintou Sacko is director of Accueil francophone du Manitoba. They are co-authors of the full report: Les immigrants face au logement à Winnipeg : Cas des nouveaux arrivants d’Afrique francophone.

by Errol Black

Canada’s Employment Insurance (EI) System has been much in the news in recent weeks. The main issues are long delays in processing EI claims resulting from the Harper government’s attempts to automate and depersonalize the way claims are processed, and increases in EI premiums effective January 1.

A December 17 report in The Globe and Mail by Gloria Galloway, titled “EI cheque delays fuel pre-Christmas client outbursts,” tells the story of how the service provided by Service Canada workers has been undermined because of the elimination of hundreds of jobs in 2011: “[Service Canada] workers say the federal government’s [elimination of processing agents] is forcing some jobless Canadians to wait months for their first benefit cheques. And the shrinking staffing levels at Service Canada call centres have created phone lines so overloaded just one in three callers actually reaches an agent. That means more people are turning up at the centres to find out when they will get paid.” Galloway notes that Diane Finley, Minister of Human Resources and Skills Development, claims the elimination of jobs is part of an effort to move from a “paper system to one that is automated.” Service Canada employees who are providing the service suggest this is not true; the system has been automated for four years, now they’re getting major cuts to jobs.

In an interview with Bruce Owen of the Winnipeg Free Press (“Welfare fills gap as jobless wait for EI,” December 30, 2011), Neil Cohen, executive director of Winnipeg’s Community Unemployed Help Centre, confirmed that it is the Services Canada employees who are telling the truth about what’s causing the EI claims crisis, and not Diane Finley. Cohen also explained that one of the consequences of the long delays in getting their claims processed is that many unemployed workers are forced to turn to Manitoba’s social assistance program to tide them over until they get their EI cheques. When Cohen was asked if there was a solution to the problem he said there was: “They’re laying off staff. They’re closing call centres. They’re closing claims-processing centres. They’ve prohibited staff from working overtime, so yes there’s a fix…”

The comments made by Service Canada workers and Neil Cohen were echoed by Pat Martin in a story in the Winnipeg Free Press on December 31, 2011 (Bruce Owen “Claim-filing logjam has MP furious with feds“): “Our office has been inundated with complaints from people who simply can’t access [EI]. You can’t consolidate and cut back Service Canada and not have a corresponding [negative] impact on service.”

This is indeed a sad story, especially for the tens of thousands of workers who are dependent on EI to tide them over the rough patches in their employment experiences. To add insult to injury, on January 1 the Harper government raised the price to employees for these deteriorating services to 1.83 per cent per hundred dollars of insurable earnings from 1.78 per cent.

It seem clear that the Harper government doesn’t give a damn for the misery and grief its policies and practices have caused unemployed workers. Nor apparently do most provincial and municipal governments that also have unemployed citizens in their jurisdictions. The City of Brandon did raise the issue of cuts to staff and services in a letter to Ottawa in June 2010. Ottawa dismissed the concerns as unfounded and said that service to unemployed workers would be improved.

What is to be done?

A place we might start is to organize unemployed workers, trade union members and others to make formal presentations to MPs, MLAs and Municipal Councillors and informal representations through information picketing. We must demand immediate improvements in service, and also the adoption of reforms to the EI system as proposed by the CLC and affiliated bodies. This would not only be a timely response to the plight of the unemployed, but it would also be a useful way to prepare ourselves for the intensifying struggles yet to come as the Harper government moves forward with austerity measures that will undoubtedly see a further downsizing of government in addition to further changes to the tax system that will disproportionately benefit the rich in Canada.

Errol Black is a member of the CCPA-MB board.

by Errol Black and Jim Silver

Each of us read Steve Brouwer’s Revolutionary Doctors (MR Press, 2011) the same week the media reported average gross fee-for-service earnings of Manitoba doctors at $298,119. The media also reported, again, that many Canadians do not have access to a family doctor; that some specialists are in short supply; and that health conditions in many Aboriginal communities are appalling.

While we are fervent supporters of Canada’s Medicare system, we think there is much to be learned about health care from Brouwer’s book.

First, Cuba produces large numbers of high quality health care providers, including doctors—more doctors per capita than any country in the world. This is a tribute to the quality and cost—free tuition—of their entire education system. The benefits to the Cuban people are reflected in two key health indicators: average life expectancy in Cuba at 77.7 years, while behind Canada at 81.4 years, is on a par with the U.S. and higher than most countries in the Americas; the infant mortality rate (number of deaths of children under one year per 1000 live births) at 4.90 is the same as Canada at 4.92, and less than the U.S. at 6.06.

Moreover, at Cuba’s Latin American School of Medicine, established in 1998 as part of the Cuban vision of a “caring socialism” rooted in international solidarity, large numbers of international students are studying to be doctors. This includes 23 Americans who enrolled because they are unwilling to take on the $150,000–200,000 in debt to pay for a U.S. medical degree, and are attracted by the obligation, in return for free tuition, to return home to practice medicine in poor communities.

Second, large numbers of Cuban medical personnel are sent around the world in response to natural disasters. Cuba’s medical team was particularly important in responding to Haiti’s January, 2010 earthquake, for example, although it earned them virtually no media coverage. The highly publicized U.S. hospital ship that anchored off Haiti, the USNS Comfort, performed 843 medical operations; Cuba’s medical brigades performed 6499. Meanwhile 547 Haitians graduated from Cuba’s Latin American School of Medicine between 2005 and 2009, and more will continue to graduate year after year.

Third, and the main focus of this book, Cuba sends physicians and other health care professionals to Venezuela in return for much-needed oil. Cuban medical practitioners work and live in Venezuela’s barrios. From 2004 to 2010 one Cuban program “continually deployed between 10,000 and 14,000 Cuban doctors and 15,000 to 20,000 other Cuban medical personnel—dentists, nurses, physical therapists, optometrists, and technicians,” to work among the poor. In the barrios the Cuban health care workers practice primary health care, and promote a holistic and preventative approach—Medicina Integral Comunitaria (MIC), or Comprehensive Community Medicine (a concept, Brouwer notes, that appealed to health experts and some medical schools in Canada and the U.S. when first proposed 1978, but that was abandoned in the pursuit of profits in ‘health care markets’).

Cuban doctors work directly with Venezuelan medical students in the morning; the students take medical classes in the afternoons. The medical training, which is state of the art, is extremely demanding. Yet large numbers of Venezuelans—30,000 as of 2011, including many of the poor who have longed to be doctors but have never had the chance because of the huge cost of medical education—are now studying to be doctors.

Most want to practice as the Cubans do: meeting the needs of low-income people in the low-income communities long neglected by the Venezuelan medical establishment; promoting a holistic and preventative form of medicine; and working in the context of the values that are a central part of Cuban medical practice.

Time and again Brouwer recounts examples of the egalitarian values that guide the Cubans’ medical practice. He describes the shameful policy implemented in 2006 by George W. Bush, called the Cuban Medical Professional Parole Program. It is aimed at inducing Cuban medical personnel practicing grassroots medicine in poor communities in more than 100 countries to defect. Brouwer estimates that a mere 2 percent of Cuban medical personnel practicing outside Cuba have accepted offers of much more money. The rest, the vast majority—not the Occupy Movement’s 99 percent, but a close 98 percent—reject these monetary inducements. They believe in what they are doing, and in the values that are such a central feature of their practice.

We wonder if Cuba’s world class medical emergency team should be invited into Attawapiskat and other Aboriginal communities in which Canada has long violated residents’ human rights. (The Cuban team was poised to assist victims of Hurricane Katrina in New Orleans in 2005. George W. Bush, whose lackadaisical response to Katrina is well known, rejected the offer. Would Prime Minister Harper similarly refuse a Cuban offer?) We wonder why many more Canadians are not being trained—without amassing huge debts—to become doctors, so that all Canadians who need health care can receive it, and all Canadians who want to do meaningful work, and who have the necessary abilities, can do so. We wonder why the values that inspire Cuban doctors and health workers—and that inspired the creation of our Medicare system in Tommy Douglas’ Saskatchewan—can’t be adopted by governments and the medical establishment in Canada.

We don’t know what is likely to happen in Cuba in the future. But for over half a century and against overwhelming odds, Cuba has developed educational and health care systems that stand head and shoulders above anything practiced elsewhere in the Americas, including the U.S. and that are a tangible expression of a system committed to the egalitarian principles of developing the capacities and capabilities of all people.

In these hard times, this book and the work it describes are an inspiration for everyone seeking alternatives to the dominant values and practices in our health care system, and in Canadian society generally.

Errol Black and Jim Silver are members of the CCPA-MB board.

Follow us!