The Fiscal Responsibility and Taxpayer Amendment Act, Bill 27, Manitoba

Presented by Lynne Fernandez, Errol Black Chair in Labour Issues, CCPA MB. Submitted October 24, 2018.

The Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA) is an independent research institute concentrating on economic and social issues. We are pleased to be able to comment on Bill 27 this evening.

CCPA has been engaged in balanced budget legislation (BBL) from its inception in Manitoba, and before we get to the specific amendments in Bill 27, we feel it necessary to first reiterate our opposition to the legislation.

BBL has a strong appeal to those who do not believe that government has a role to play in stabilizing our economy. But economic crises are unavoidable in our system, often from the irresponsible behaviour of the financial sector, as we saw with the 2008 crisis. With governments unwilling to face the fact that taxes have been cut too much, leaving us with a shortage of revenues to deal with these challenges and even closer-to-home social emergencies , it is unrealistic to expect that deficit spending can be avoided indefinitely.

The very spirit of BBL goes against basic principles of Keynesian economics of using government spending and taxing policies to maintain economic stability. When a crisis hits and the private sector retreats, the government must step in to stabilize demand and prevent massive unemployment. It could also reduce taxes at that time to stimulate demand. When the crisis ends, government spending should return to normal levels and taxes should be increased to pay down the deficit.

As the BBL stands, it does not allow for deficit spending to prepare for future crises such as are likely to occur with climate change. That said, in no way do Keynesian principles promote endless stimulus spending or tax reductions: a responsible government accountable to voters must use deficit spending prudently.

Modifications of the BBL have at least allowed for emergency spending for natural disasters, but governments’ refusal to remove the requirement for a referendum around raising taxes dooms governments to either underspend and/or run deficits when emergencies hit.

Making matters worse are the perverse incentives in Bill 27 which will penalize Cabinet Ministers when the deficit is not decreased by at least $100M/year. This incentive assumes that Ministers are either not being responsible and/or that no situation will occur that requires a larger deficit, or impedes its reduction. Should another financial crisis occur, or should action be required to improve services in a crucial area, will this government not respond because Cabinet Ministers don’t want to be fined?

Adding insult to injury is the “Jubilee Clause” which will refund any fines paid once the deficit is eliminated. This amounts to another perverse incentive for government to not respond responsibly to any crises that may arise. These disincentives, combined with the need for a referendum to raise taxes, turn Keynesian principles of responsible budgeting upside down.

These incentives also encourage the deficit to be paid down faster than needed and encourage cuts to front line services. Given the considerable challenges segments of our population face, it would be more responsible to base spending decisions on how to reduce poverty and ensure sufficient public services rather than on whether Cabinet Ministers are going to get their penalties refunded.

Finally, notwithstanding the ineffectiveness of BBL overall, the idea of refunding Cabinet Minister’s penalties would seem to defeat the purpose of the penalty in the first place. Every time I get caught speeding or running a red light, I have to pay a fine. Fair enough; I’ve broken the law. If I then go a year without breaking the law, I do not expect a refund for my past misdemeanours.

In sum, BBL has been modified in this province and others out of necessity because when governments voluntarily or legislatively constrain themselves from raising taxes when required, deficits become necessary. The amendments in Bill 27 are an attempt to fix this structural problem by pushing Cabinet Ministers to put their personal finances ahead of making responsible budgeting decisions.

The so-called Jubilee Clause gives Cabinet Ministers an escape hatch that no other Manitoban has access to. Should government not make responsible budgeting decisions because of these amendments, Manitobans will be the ones who suffer.

This bill passed Committee stage on October 24, 2018, the night of civic elections across Manitoba. It moves toward Royal Ascent.

By Molly McCracken

Climate change poses extreme risks for all our families, communities and province. As elected officials you represent all Manitobans and have a responsibility to act in the face of threats.

The United Nations International Panel on Climate Change says we only have 12 years to change to avoid catastrophic impacts of climate change[1].

The Prairie Climate Centre at the University of Winnipeg’s Climate Atlas for Manitoba finds that we are a trajectory for a high carbon future[2]. This will impact agriculture via more droughts. Hotter summers will result in more, larger and intense forest fires. Manitoba will have floods in the spring and then droughts in the summer. These will have huge economic costs to the province, the business sector and in human suffering. This is a catastrophe in the making unless we make drastic changes now.

- We must work back from our goal

In 2016 in Paris, Canada committed to reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 30 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030.

Many scientists were critical of the Paris commitments not going far enough. The United Nations[3] itself audited the Paris agreement and said that it would only limit rising earth’s temperatures to 3 degrees Celsius warmer by 2100, relative to preindustrial levels.

So even what was agreed to in Paris does not go far enough. But it’s what we have to work from as a goal.

This past August Harvey Stevens, a well-respected former civil servant and quantitative researcher released “An Analysis of Manitoba’s Proposed Plan to Reduce Greenhouse Gas Emissions as Contained in the Manitoba Climate and Green Plan”[4] published by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives Manitoba.

Stevens writes that the Paris commitment to Manitoba means that by 2030, the GHG emissions for that year have to be 14,158 Kt. They were 20,936 in 2016. They must be reduced substantially but the Made in Manitoba Climate and Green Plan falls short of this goal:

- It does not address the fixed goal of GHG emissions by 2030 but instead uses cumulative reductions over time. It sets no cumulative reduction target. This is not the standard method of reporting; all countries report to the United Nations using total annual emissions.

- It sets out five cumulative pathways, the most aggressive falls short of the needed 2030 goal by 1,400 kt or 1.4 million tonnes. The social cost of carbon is estimated at $50 – $200 per tonne[5] on agriculture, forests, water availability and pests[6]. This means this shortfall could cost Manitoba and Canada $70 million to $280 million dollars.

- The carbon accounting system described in sections 5, 6 and 7 of the Act is not clear on how it will measure how Manitoba will be “Canada’s cleanest, greenest and most climate resilient province”.

Stevens reviewed the EC-Pro report commissioned by the province for the Climate Plan. This report compared the current federal plan of $10/ tonne / year increase between 2018 and 2022 with no further increase to one that continuously increases up to $130/ tonne by 2030. The EC-Pro numbers find that the price on carbon would have to continue to increase $6.78/ tonne/ year to prevent an increase in GHG emissions.

Stevens found that the reports commissioned by the province said that a carbon tax is needed and it must be high enough to reduce emissions. But instead this government is ignoring these reports and backed out of the provincial carbon tax.

Now that the federal backstop will apply to Manitoba, the provincial government should do nothing more to fight this.

- Climate action must be fair

The Ecofiscal commission’s report Provincial Carbon Pricing and Household Fairness[7] identifies that a price on carbon affects household budgets differently as it increase the prices of emissions-intensive goods and services, which represent a larger share of expenditures for lower-income households[8]. The Ecofiscal commission estimates the cost of a $30 carbon tax on a household with incomes below $50,000/ year is $288/ year. The federal “Climate Action Plan” incentive will pay a family $685 when the carbon tax rises to $30/ tonne in 2021[9]. It is more than sufficient to cover the costs for low income households; there is plenty of room to compensate households and retain carbon tax revenue to invest in green infrastructure to help households get off of carbon. Households alone will have a hard time doing this.

A price on carbon is like the stick, and it must be matched with the carrot – help for families to get off carbon. These are items to reduce carbon costs by supporting better, more affordable public transit, affordable local food and home energy retrofits.

- The Climate and Green Plan cannot be done in isolation of other government policy.

This act replaces the Sustainable Development Act. Important provisions will be lost and should be reinstated:

- Regulatory codes and standards for green buildings and green vehicles

- Principles and Guidelines for Sustainable development. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals to 2030 are widely used, by the United Way Winnipeg and Economic Development Winnipeg locally. These should be used.

Currently the Plan completely ignores government’s actions that will increase GHG emissions:

- The Minister of Agriculture wants to increase the number of cattle from 400,000 to 750,000. This will increase GHG emissions 789 kt / year for a social cost of carbon of $39 million – $157 million

- The hog industry is calling for 1.2 million more hogs over the next 5 – 10 years. This will add an additional 251 kt/ year for a social cost of carbon of $12.5 million – $50.2 million

There is nothing in the plan to address these new emitters. The cumulative emissions reduction metric described in 7(2) only considers measures that lead to a reduction in emissions, not those that lead to an increase in emissions such as an increase of cattle or hogs.

Annual emissions by sector should be included in the reporting.

Moreover, there are currently no details in the Climate and Green Plan[10] on implementation.

Recent government actions undermine these goals. For example, unilaterally ending the 50/50 cost sharing agreement with the City of Winnipeg on transit, a loss of $5 million in 2018[11]. Transit ridership is lower today than 20 years ago[12]. Transportation is the largest GHG emitter in Manitoba[13] and we need to improve public transit to get people out of their cars across the province.

Earlier this month William Nordhaus and Paul Romer won the Nobel Prize in economics for their work studying the consequences of climate policies such as carbon taxes. Their key recommendation is that governments, corporations and households should have to pay a rising price on carbon emissions. This is what’s called internalizing the externalities of the costs of carbon to all of us.

British Columbia has had a carbon tax since 2008. The tax covers most types of fossil fuels. According to Professor Stewart Elgie of the University of Ottawa and Richard Lipsey of Simon Fraser University:

“Since it came in, B.C.’s total use of fuels has dropped by 16.1% (2008-13). By contrast, in the rest of Canada fuel use went up by 3% over that time. B.C.’s dramatic drop since the tax marks a big change from the previous eight years (2000-2008), when its fuel use was actually rising slightly compared to the rest of Canada’s. (These results reflect the latest available Statistics Canada data, and were published in a leading research journal.)[14]” BC’s GDP outperformed the rest of Canada’s since the carbon tax began.

- Action is an insurance policy on the future. The insurance sector warned of the effects of climate change as early as 1973, and continues evolving its business model, including increasing rates, to adapt to the changes. The Fort McMurray fire is attributable to climate change[15] and cost the insurance industry between $5 billion and $9 billion, which is passed on to property owners and businesses.

If anti-tax business interest groups think that any government can prepare for climate change – including the disproportionate impact it will have on the poor, and creating green infrastructure – all without somehow increasing revenues- it needs to get a reality check from those in the insurance sector who are increasing their revenue as they understand the world we find ourselves in[16].

And yet this provincial government is bent on placating these business interests and cutting taxes and bringing down the deficit at the same time. This austerity at a time of climate crisis is irresponsible and will create undue burden on future generations.

The province could do a number of things to bring in new revenue: keep the PST at 8% and direct money to make life affordable in a post-carbon Manitoba and introduce mobility pricing so cars pay the full cost of using roads. There are other options for revenue to incent behaviour change to fight climate change. The current trust fund the province has created will yield only peanuts compared to the scale of the problem.

Thank you

CCPA MB Research Associate Mark Hudson also presented on Bill 16 as well, see “Manitoba’s Climate and Green Plan: a Catastrophic Failure of Leadership“

Bill 16 was passed by passed committee on October 25, 2018. It moves to the Report Stage, one step closer to Royal Assent & becoming law.

[1] http://www.ipcc.ch/report/sr15/

[2] https://climateatlas.ca/sites/default/files/Manitoba-Report_FINAL_EN.pdf

[3] https://news.nationalgeographic.com/2017/10/paris-agreement-climate-change-usa-nicaragua-policy-environment/

[4] https://www.policyalternatives.ca/sites/default/files/uploads/publications/Manitoba%20Office/2018/08/MB%20Climate%20and%20Green%20Plan%20Analysis.pdf

[5] Ackerman, F. and E. Stanton, 2011. Climate Risks and Carbon Prices: Revising the Social Cost of Carbon, published by Economics for Equity and Environment network. Available at: www.e3network.org/social_cost_carbon.html

[6] http://ec.gc.ca/cc/default.asp?lang=En&n=BE705779-1

[7] http://ecofiscal.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/Ecofiscal-Commission-Provincial-Carbon-Pricing-Household-Fairness-Report-April-2016.pdf

[8] Households below $29,783/ year will spend $155/ year on a $30 price of carbon or 0.7% of their income. Households earning up to $45,732 will spend $288 or 0.6% of income. They conclude that while there is a cost to households, this does not preclude action as we must act to address climate change.

[9] https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/climate-change/pricing-pollution-how-it-will-work/manitoba.html

[10] https://www.gov.mb.ca/asset_library/en/climatechange/climategreenplandiscussionpaper.pdf

[11] https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/winnipeg-transit-funding-campaign-1.4274370

[12] https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/winnipeg-declining-bus-ridership-statistics-canada-1.4429825

[13] https://climatechangeconnection.org/emissions/manitoba-ghg-emissions/manitoba-transportation-ghgs/

[14] https://business.financialpost.com/opinion/b-c-s-carbon-tax-shift-works

[15] https://www.macleans.ca/society/science/did-climate-change-contribute-to-the-fort-mcmurray-fire/

[16] https://winnipegsun.com/news/national/municipal-budgets-challenged-by-infrastructure-needs-and-climate-change-not-overall-labour-costs

By Ellen Smirl

A year after announcing a 25-cent a trip fare increase, mayoral candidate Brian Bowman has promised to create a low-income transit pass if he is re-elected mayor on October 24th. This is great news because waning government support at the provincial level through a funding freeze and the fare increase has led to poor service, unaffordable fares and declining ridership.

Many low-income Winnipeggers and those in the inner city rely on public transit with no other options. Unaffordable transit means not being able to get to work, yet another added cost to already stretched grocery budgets, get to medical appointment or visit friends and families.

Winnipeg Transit fares are currently structured as a flat fee. This means that people with lower incomes are paying proportionately more of their income on fares. The recent fare increase exceeded the rate of inflation and is much greater than any increases in government income assistance programs or the minimum wage rate.

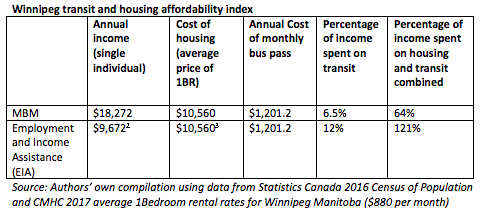

Individuals living at the Market Basket Measures threshold spend 6.5 per cent of their income on taking transit, however when the cost of transit and housing is combined that figure jumps to 64 per cent. Individuals receiving EIA would have to spend more than they receive in order to afford both housing and a transit pass. This means that many Winnipeggers are making trade-offs between getting where they need to go and having a decent place to live.

Ensuring that people can afford to take the bus is an important tool in fighting poverty and improving health outcomes. Additionally, ninety per cent of attacks against bus drivers involve fare disputes which demonstrates that a low-income transit pass will not only make fares more accessible to people living on low-income but also make a safer workplace for drivers.

Lessons learned in other jurisdictions have shown that the structure and design of a low-income pass program determines how effective it is at reducing transit poverty.

Determining eligibility matters. Many community agencies have said that their clients have to repeatedly prove their low-income status to qualify for a variety of subsidies and that this continual need to jump through hoops represents major barriers for their clients. The City of Calgary offers the Fair Entry Program, which is a single application process to access multiple programs and services including the low-income bus pass as well as the recreation fee assistance and the low-cost spay and neuter program. We have also heard that some low-income individuals struggle to prove their identity and some municipalities have allowed discretion for community-based organizations (CBOs) that have good relationships with their clients to administer the passes on an honours-based system.

While most low-income programs generally offer a discount of somewhere around 50 per cent many evaluations of these programs found the cost was still too high for many. Calgary offers a sliding scale of $5.15 to $51.50 per month based on income.

Anyone receiving social assistance should receive a pass at no cost because any amount is too much given the present inadequacy of the basic needs allowance for actually meeting basic needs. This should not result in any reductions in benefits that people currently receive. New refugees should also receive a free pass as is offered in Grande Prairie Alberta.

Through conversations in the community we have heard that kids are not going to school because their families cannot afford a bus pass. Low-income families should receive free bus passes for school-aged children. Other options include investigating the viability of a family-pass. Any fare reduction strategies should not be limited to travelling in off-peak hours, nor certain days of the week.

Finally, the specifics of design of the low-income pass should occur in consultation with community-based organizations (CBOs) who serve the targeted population. Low-income individuals themselves should also be consulted to ensure that the pass meets their needs. CBOs should be involved in the planning, implementation and evaluation stages.

Establishing an affordable transit program is only the first step. Addressing transit poverty and its consequences means creating a transit system that is safe, reliable, accessible and affordable. Fare reduction strategies should not come at the expense of any reduction in service. This will require broad-scale transit investment. This means lobbying the province to restore and increase the 50-50 funding for Winnipeg Transit operations. While the Provincial government recently scrapped the provincial Carbon Tax, the federal backstop will still apply and a portion of this should be invested in public transit.

Finally, the City makes choices about where to invest money. Public transit should be treated as a valuable public service in the same vein as libraries, community and recreation centres, and public health. It is time for the City of Winnipeg to demonstrate leadership on transit affordability while simultaneously advocating for better funding from other levels of government.

Transit and transportation equity and poverty is the focus of the 2018 State of the Inner City Report. Ellen Smirl is the CCPA MB researcher on this report.

By Mark Hudson

Last week, the Manitoba government announced it would amend Bill 16, the “Climate and Green Plan,” to eliminate its flat $25/tonne carbon tax, leaving it essentially empty of any real action on climate change. Just a few days later, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)—the UN body in charge of informing policy-makers about the science of climate change—issued a landmark report saying that without urgent and unprecedented action to rapidly bring down greenhouse gas emissions in the next dozen years, we will face catastrophic consequences. The contrast between the call by the UN to rise to our moral responsibility to mitigate climate change, and Premier Pallister’s gutting of the already-too-weak Bill 16 couldn’t be more jarring, or speak any louder about the failure of leadership in our province.

Climate change is the defining challenge of our time. Dealing with climate change is not equivalent to, say, achieving a balanced budget—whatever the merits of that goal, but about the survival of entire species and hundreds of millions of human lives. The statement about staking our future is easy to let wash off, because we hear it so frequently. But in this case, it is not catastrophism or scare-mongering. It is a clear-eyed reckoning with the increasingly ominous signals being read by a vast community of earth and climate scientists, and by people on the front lines of warming. So, we have an array of facts before us as follows, some of which are, to the government’s credit, palely reflected in the preamble to Bill 16.

1) Climate change is manifesting itself now. Model projections for many of the consequences of warming have proven conservative in terms of their timing and scale. This is not a fight we can put off—and in fact we should have been engaging in it decades ago. We are late as it is.

2) The consequences of our failure to engage meaningfully are difficult to overstate. They are too many to list here, but to summarize the vast field of research on this, they are civilizational in scale. Should we continue to pussy-foot around climate change, there will be hundreds of millions of victims—victims of dislocation, sickness, and death. Already, just to take one small indicator, the World Bank estimates that there will be 140 million internally displaced people resulting from climate change by 2050, and millions more internationally. Also of note for those whose pulse is quickened by costs expressed in dollar figures, rather than human lives and ecological destruction, is that we’ll be knocking 13% off of global GDP by 2100, even sticking to a 2 degree target. The costs of adapting to increased severe weather run into the hundreds of billions. A failure to comply with the goal of keeping the world below a 1.5 degree average warming will result in much, much worse. A conservative estimate of the global costs of just coastal flooding is $14 trillion.

3) We are well aware of what’s causing this. The hard math that drives the arithmetic of climate change is unforgiving and unambiguous. The IPCC’s carbon budget makes it as plain as it can be. If we continue to allow people to dig up and burn fossil fuels without a clear and rapid plan to transition off of them we are headed for catastrophe.

What these facts mean together is that in refusing to hold to account those responsible for continuing to pump out greenhouse gases we are knowingly contributing to the dislocation, misery and death of hundreds of millions around the world. It is happening now and will accelerate in the near future. These are not comfortable facts, and a less comfortable conclusion, but they are unassailable, and confronting them is the burden of leadership.

Leadership is required here because a meaningful response to climate change (despite the Climate Plan’s repetition of the myth that for individuals, there is “always a greener choice”) actually requires collective, policy-led changes. Getting off of fossil-fuels—an absolutely necessary condition of staving off the consequences we have been warned about and are now beginning to experience—does not entail individual decisions to simply turn off the carbon tap, because our economies, our physical infrastructure, and the ways we move ourselves, feed ourselves, and keep warm are soaked in oil. We often hear people who point out this reality go on to say “so, fossil fuels will be a part of how we do things for a long time yet,” and certainly many organizations behave as though that’s true. Large emitters will continue to behave that way unless compelled to do otherwise. Fortunately, there are feasible, though difficult at this point, ways of transitioning off fossil fuels.

These can and should entail the up-skilling of workers in currently high-carbon sectors, as, for example, oil patch workers in Alberta are doing through the organization Iron and Earth, and the protection of low-income families who will have some of the costs of transition passed onto them. Some cities and states elsewhere are showing what can be done: Paris’ climate plan, to take just one example, has over 500 initiatives to make it a vibrant, livable, carbon-neutral city by 2050. Local and sub-national governments are using public purchasing power to encourage transitions to low carbon vehicles, investing in efficient public and active transportation to move people through our cities, encouraging zero-carbon energy systems through targeted public investment, providing subsidies or support for demand side energy management, retraining workers in carbon-intensive sectors like pipeline construction, putting them to work in good jobs building the new infrastructure required for a zero-carbon economy, and providing research and extension for zero-emissions or net-negative agriculture. These bottom-line requirements of our collective responsibility for climate change require policy leadership.

If the “Climate and Green Plan” is the sum total of Manitoba’s response—and so far it seems to be—it represents an epic, even catastrophic failure of such leadership. If we are in a fight with climate change, we’re sending a kindergartener out against a title fighter, and should only expect a beating.

There was much to say about the insufficiency and poor design of the carbon tax that initially appeared in Bill 16, but which has now been cut out. It was utterly insufficient to produce any meaningful change, had no plan to use revenues in innovative ways to encourage a shift off of fossil fuels, and failed to protect low-income Manitobans from regressive effects. However, it was a signal that Manitoba was at least willing to take a baby step. With the removal of the carbon tax, we now have a bill utterly devoid of significance or effect.

Of course, Manitoba is not in this alone. We are, on the grand scale of greenhouse gas emissions, a small player. We contribute about 3% of the national total, and Canada as a whole emits about 1.6% of the global total. That’s not to say we are carbon-pinchers. On a consumption basis, Canada is the 9th largest emitter globally. Per capita, each Canadian in 2016 contributed over 20 tons of CO2—masking huge regional inequality, with Alberta pumping out by far the lion’s share. Premier Pallister justified the removal of the carbon tax by saying that we should be given credit for our investments in Hydro. Our electricity source is, indeed, relatively low-carbon. Yet still in 2016 Manitobans managed to produce about 16 tons of CO2 equivalent per person—well over 10 times the global equitable level. Looking at territorial emissions, our neighbours to the east in Ontario and Quebec perform much better. Our emissions from agriculture, after some small progress from 2008-11, have been on the rise since, and are almost 40% higher than they were in 1990. On transportation, our other major emissions source, emissions from 1990 are up as well, almost 70%. There is simply no basis for the claim that we are already pulling our weight—and one can only imagine how such claims are heard in a place like Tuvalu, being swallowed by rising seas, by people in the Philippines, hammered by superstorms made more powerful and frequent by climate change, or in the arctic, which has already warmed 3.5 degrees on average since the beginning of this century, and where communities are slumping into the sea.

Due to our small size, we might say that there are others who should be leading the way–others who are more culpable than us. The problem with this logic is well-known, and derives from the global and collective nature of climate change. The necessary political condition for a coordinated and global response to climate change—one that is adequate to the enormous nature of the challenge—is visible cooperation. Everyone must see that everyone else is pulling as hard as they can pull toward the objective. Laggards—the most obvious being the Trump administration in the US, but also the Manitoba government’s comrades in resisting climate action, like Premier Doug Ford and Opposition Leader Jason Kenney—don’t just undermine the project through their refusal to reduce their own emissions. They undermine it by signalling that efforts won’t be reciprocated, encouraging others to minimize their efforts in turn. While we can’t do anything about Mr. Trump and his Canadian counterparts, we can send a different signal—one that demonstrates that we are willing to lead, rather than foot-drag.

If everybody follows the climate resisters’ lead, the logical endpoint is crystal clear. A provincial government concerned enough about the deficit situation to cut funding to education and health care should be very concerned about the ballooning future costs to the public of adapting to the 3.2 degree warming forecast for this province under even a low-carbon scenario. Now is not the time for penny wise, dollar foolish public policy. If we peg our ambition to those who do nothing to combat climate change, the future economic costs will be astronomical.

The global effort to combat climate change is already well behind schedule. Funding for mitigation and adaptation has not materialized. Reductions are less than needed. This global effort, of course, is composed entirely of policies and programs like this one. It is ultimately legislation and action at local levels that make up the global effort.

Refusal to join this fight is not protecting Manitobans. It consigns us to an unsustainable and laggard economy from which future investment will shy. In June, a group of 288 global institutional investors controlling $26 trillion in assets called the G-7 members out for their lack of ambitious climate change action. Investors are looking for policy environments in which green investment is welcome. The Manitoba government’s stance on climate change generally and its withdrawal of the carbon tax in particular not only costs us millions in the short term, but sends a loud signal that Manitobans prefer to stick with the fading and destructive fossil economy of the 20th Century.

It is well past time to acknowledge the stakes of climate change not in substance-less preambles but in the form of policy that will actually make a difference. The current generation should not have to face the 3 degree average warmed world in store should governments limit themselves to the current national pledges under the Paris Agreement. Nor should our children have to deal with the 6 degree warmer planet that we are actually on target to realize, as governments put forward tragically insufficient legislation like Bill 16. I urge this government to look straight on at these stakes, acknowledge our moral responsibility in doing our part to avert the worst, and to deliver to Manitobans a piece of legislation that intends to make a meaningful contribution. That contribution should embrace and support a just transition off of fossil fuels, help us move toward a 21st century economy, and be reflective of our unwillingness to make others suffer on our behalf.

Mark Hudson, CCPA-Manitoba Research Associate; Associate Professor of Sociology, University of Manitoba.

This article is Hudson’s committee presentation on Bill 16: The Climate and Green Plan. A Fully referenced version available upon request.

By Ellen Smirl

Key Findings:

• Access to affordable, reliable, safe, and accessible transportation options is an important tool to help people lift themselves out of poverty and build a healthier city.

• Greater investment in transit and active transportation by all levels of government is needed

• Ensuring the benefits of investment are equally distributed needs to begin in the design stage

Transportation options in Winnipeg are not meeting the needs of the people who need them most. While significant discussion around transportation in Winnipeg is occurring, much of the current discussion focuses on how to attract new ridership and/or reduce congestion and greenhouse gases (GHG). Many people in Winnipeg however are struggling simply to get to work, school, grocery stores, medical appointments, and social activities.

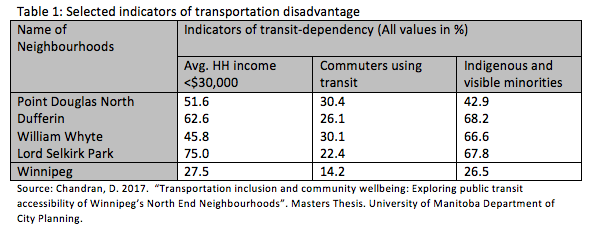

While statistics for transportation disadvantage by neighbourhood cluster does not exist for Winnipeg, one recent study concluded that residents of the North End are more likely to be transportation disadvantaged than the rest of the city. The following table shows the connection between lower income neighbourhoods and reliance on public transit. Indigenous people and visible minorities are also more likely to rely on public transportation. Major indicators of transportation disadvantage include non-ownership of a vehicle, low-income, and minority ethnic identity.

Many transportation advocates are calling for increased equity when it comes to transportation planning. Transportation equity is the fair distribution of the benefits and costs, and in a way that meets the social and economic needs of the greatest number of residents, and especially those most vulnerable. Ensuring that everyone, regardless of physical ability or ability to pay has access to public transit and active transportation options is an important part of fighting poverty and inequality in Winnipeg.

To build a transportation system that works for most vulnerable we need to fully understand the challenges. The State of the Inner City Report 2018 (forthcoming) spoke with twenty people living in Winnipeg’s inner city and asked them about the barriers they experience in getting where they need to go. We also hosted a townhall discussion at the Thunderbird House on September 25th 2018 where all inner-city residents were invited to attend. This is what we heard.

Challenges

When it comes to taking transit, many people spoke about not being able to afford the fare. In January 2018 Winnipeg Transit raised fares by 25 cents in response to a $10M operational budget shortfall, which occurred when the Province froze their contribution to Winnipeg Transit at 2016 levels. Many people we spoke with said that they would sometimes go without food to afford a bus pass so they could get to work, while others said they would sometimes walk long distances so they could afford to buy groceries. This is a trade-off no one should have to make.

All of the people we spoke to said that schedules and time represented a major barrier in getting where they needed to go. Many spoke about buses not being on time. This is supported by statistics with weekday on-time reliability declining from a high of 80 per cent to 74.8 per cent in 2017. One young man spoke of the challenge in taking the bus to get to his workplace. His worksites would vary throughout the city, sometimes in areas with poor bus service. Despite getting up very early he would sometimes be late to work because late buses often resulted in missed connections. Transit needs to get people to where they want to go when they need to be there.

Many people we spoke with talked about fears about walking alone at night as well as waiting at bus stops, and some spoke about concerns about safety while riding the bus. Some young women spoke about being solicited for sex in exchange for fare by cab drivers. One young Indigenous women even spoke about how she was almost abducted walking by herself at night in the inner city.

I don’t feel safe at night. Once, I was walking around and this guy, he pulled up close to me, and he tried to grab me so I punched him and I just ran.

Incorporating equity into the transportation system means that we bring in a historical understanding of the history of Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls into the planning of the system and ask ourselves, “How can we design systems to better protect Indigenous women and girls?”.

Accessibility is another major barrier for community members. We spoke with six seniors with various mobility issues and one person that is wheelchair dependent. Again, affordability and scheduling were the two biggest barriers. Many seniors and people living with a disability have fixed-incomes, which makes getting where they need to go, at times, unaffordable. Many spoke about feeling isolated and lonely, especially during the winter months. Those with mobility issues and the elderly often struggle to carry groceries which means food security is also at risk.

For people using Handi-Transit, scheduling was a major issue. Staff at a senior’s home we spoke to said that many of their residents depend on Handi-Transit to get to medical appointment but because of the high demand for services, people are often required to get to their medical appointment hours early and wait long after they are done. For people with diabetes who need to stick to a scheduled eating time, or even for those with incontinence issues, this presents dangerous and humiliating challenges.

What people need

Most other major Canadian cities have a low-income bus pass and Winnipeg should not be the exception. Ensuring that people can get to their jobs and other opportunities is an important tool in fighting poverty. Additionally, ninety per cent of attacks against bus drivers involve fare disputes which demonstrates that a low-income bus pass will not only make fares more affordable, but also make a safer workplace for drivers.

Winnipeg is currently planning for the development of a coordinated and integrated transit plan that includes a Frequent Service Transit Network, Rapid Transit and electrification. This is to be applauded. Winnipeg can do even better by integrating the Transit plan with Winnipeg’s Pedestrian & Cycling Strategies to encourage inter-modal travel. Many low-income residents supplement their transit use with walking and bike riding and they frequently said they don’t feel safe riding bikes alongside cars, nor walking through certain areas especially at night. Greater discussion about how to improve safety-besides simply throwing more police at the problem-also needs to take place.

The report of the Task Force Reviewing Handi-Transit Issues adopted by Council on Sept 21 1994 stated that the characteristics of a transportation service for physically disabled persons should be reasonably equivalent to the service provided to able-bodied persons by the regular fixed route system. Disability advocates have been vocal that the quality of Handi-Transit services is not a reasonable equivalent. Many people we spoke with said that service has eroded since the City has contracted out this service to private companies and advocates say they would like to see Handi-Transit brought back in-house.

Big picture

Other cities are investing in transit and it’s paying off. While Winnipeg spends approximately $200 per person on transit, Edmonton spends closer to $300 and Ottawa spends over $400 per person. Ottawa residents take 40 more trips per year than Winnipeggers.

Encouragingly, in June 2018 the Federal and Provincial governments announced a bilateral cost-sharing agreement that will see a $530 million investment to public transit infrastructure for Manitoba municipalities. This is great news although questions remain as to whether this agreement will be affected by the Province’s recent decision to scrap the Carbon Tax. Regardless, investment dollars in infrastructure needs to be met with investment in the operational budget. Province needs to step up and restore the 50/50 funding agreement for Winnipeg Transit operating costs. A recent poll shows that four out of five Winnipeg voters are in favour of this.

From a revenue perspective, the recently scrapped Carbon Tax would have represented an incredible opportunity to raise revenue for investment in Winnipeg Transit operations as well as improving active transportation options like developing more bike lanes and pedestrian infrastructure to get people where they need to go. While the Province’s Made-in-Manitoba Climate and Green Plan states that one of its goals is to ‘support greater use of active or public transportation’, how remains unclear.

Finally, investment in transit and active transportation needs to be undertaken with a mind towards distributing the benefits in an equitable manner. Other cities are doing this. In 2004, Denver voters approved FasTracks, a $7.8 billion transit expansion. Mile High Connects (MHC) was formed shortly after to help ensure that considerations of equity went into the planning of newly built transit lines. MHC is a cross-sector collaborative of non-profits, foundations, businesses, and government leaders in the Denver region that makes an explicit connection between public transit and health equity. Their goal is to ensure that Denver’s new transit development benefits low-income communities and communities of colour by connecting them to the services they need the most such as jobs, healthcare providers, schools, grocery stores, parks and other essential destinations.

We currently have an incredible opportunity to develop more equitable transportation policy in Winnipeg. The Winnipeg Transit Master plan request-for-proposals just closed and the Our Winnipeg plan-which includes a section on sustainable transportation- is currently being updated. The City should ensure that these plans are developed with an eye to equity so that accessible and affordable transit options are created for everyone, especially the city’s most vulnerable. With increasing suburbanization of poverty in Winnipeg, the time to embed equity policies into transportation policy is now.

Ellen Smirl is a researcher with the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives – Manitoba. Transportation equity is the theme of this year’s State of the Inner City Report. The full report and findings will be launched in December 2018.

By Jim Silver

First published in the Winnipeg Free Press September 28, 2018

In August the Free Press published an article (Safety complaints at Lord Selkirk Park, Aug. 24, 2018) that painted a very negative picture of Lord Selkirk Park, a large Manitoba Housing complex in Winnipeg’s North End. The story claimed that safety complaints had doubled in 2017, and that despite investments in the community, residents “are not seeing improvements.”

I found this disturbing, since there have been many positive changes in Lord Selkirk Park since 2005. These have been documented in various publications and in the film A Good Place to Live.

In the 1990s and early 2000s, many described Lord Selkirk Park as a “war zone.” It was a place to avoid. Starting in 2005, community development work and public investment produced dramatic changes. Lord Selkirk Park became a good place to live, with a range of educational initiatives and a strong sense of community.

So, what has happened? Have all the gains since 2005 been lost? Over a recent three-day period I spoke with 18 residents, asking them to tell me what’s happening. I also spoke with two long-time community workers, three educators, and three Manitoba Housing staff, all but one of whom work daily with residents of Lord Selkirk Park—a total of 26 people.

What became apparent is that all the previous gains are still in place. Staff at Kaakiyow, the adult learning centre, said “we’re thriving now.” The Resource Centre is a vibrant hub of community activity. Residents say the Resource Centre staff are “fabulous,” as are local Manitoba Housing staff.

There continues to be a strong sense of community. You can feel it walking around, and the people I spoke with confirmed that feeling. One resident said: “I think it’s awesome. People look out for each other.” Another said “I love the people who live here.” A community worker told me, “It’s far better than it was when we started in 2005. There’s far more good than bad here.” A resident told me that securing housing at Lord Selkirk Park was “like a godsend” to him and his family, and added that the sense of community here is “unlike anything I’ve ever experienced in my life.” Another, when asked what it’s like living here, said “it’s beautiful.”

But there is a problem. Those I spoke with are virtually unanimous that the problem is meth. “It’s a different animal,” I was told by one person. “It’s a beast,” said another. An educator told me: “What we’re seeing is a shift in the reason for crime,” which is now being “driven by meth.” Incidents of erratic, meth-fueled violence were described. It’s “making people crazy,” one resident told me. Police and social workers and community workers are all “overwhelmed,” and “everyone’s inundated.” Nobody has a real solution, and the resources to deal with the meth problem are just not there. It “came out of left field and just blew up,” one worker told me. The problem is city-wide, although it hits people who are low-income and dealing with trauma particularly hard.

The Free Press article made only passing reference to meth, even though it’s clear that meth is the real issue. The reporter spoke with two people only. Everything about the story was negative. Not a positive word was included. There is of course a long history of reporting only the negative about the North End. The old newspaper maxim, “if it bleeds, it leads,” has long applied here. All the usual stereotypes were present in the Free Press story.

People I spoke with say the story did not accurately portray their community. The article implied that Lord Selkirk Park is a failed community. This is simply not the case. The claim that residents are not seeing any improvements is false. The housing complex is full, has a wait list of people who want to live there, and has some 60 newcomer families who are doing well. The sense of community is strong, and most people I spoke with are grateful and happy to be living there.

The problem is meth. Residents and community workers are pretty much unanimous in saying so. And they told me over and over that they need treatment facilities and supports in the community.

What we’re talking about is a healthy low-income community being hit by a problem that is not of their making.

Last month’s Free Press story missed all of this. It missed the good news story about how real gains continue to be made in this low-income community. And it missed the bad news story that recent problems are caused by meth, for which insufficient resources are being made available.

We should drop the old stereotypes, and listen to what those who are closest to the issue are telling us—meth is the real problem; community-based resources are needed.

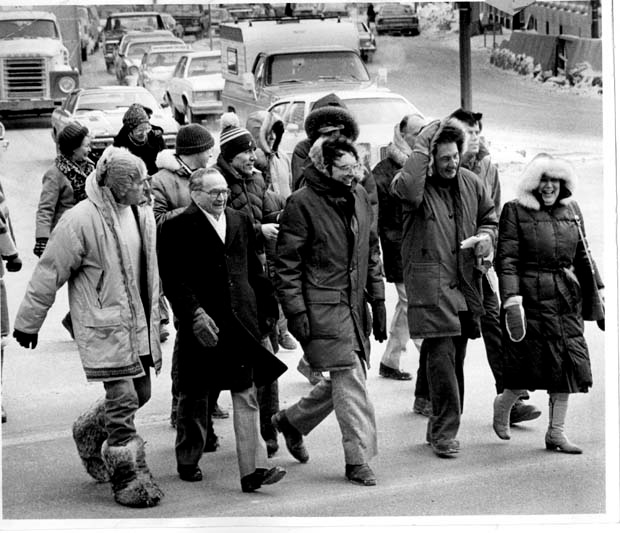

By Doug Smith

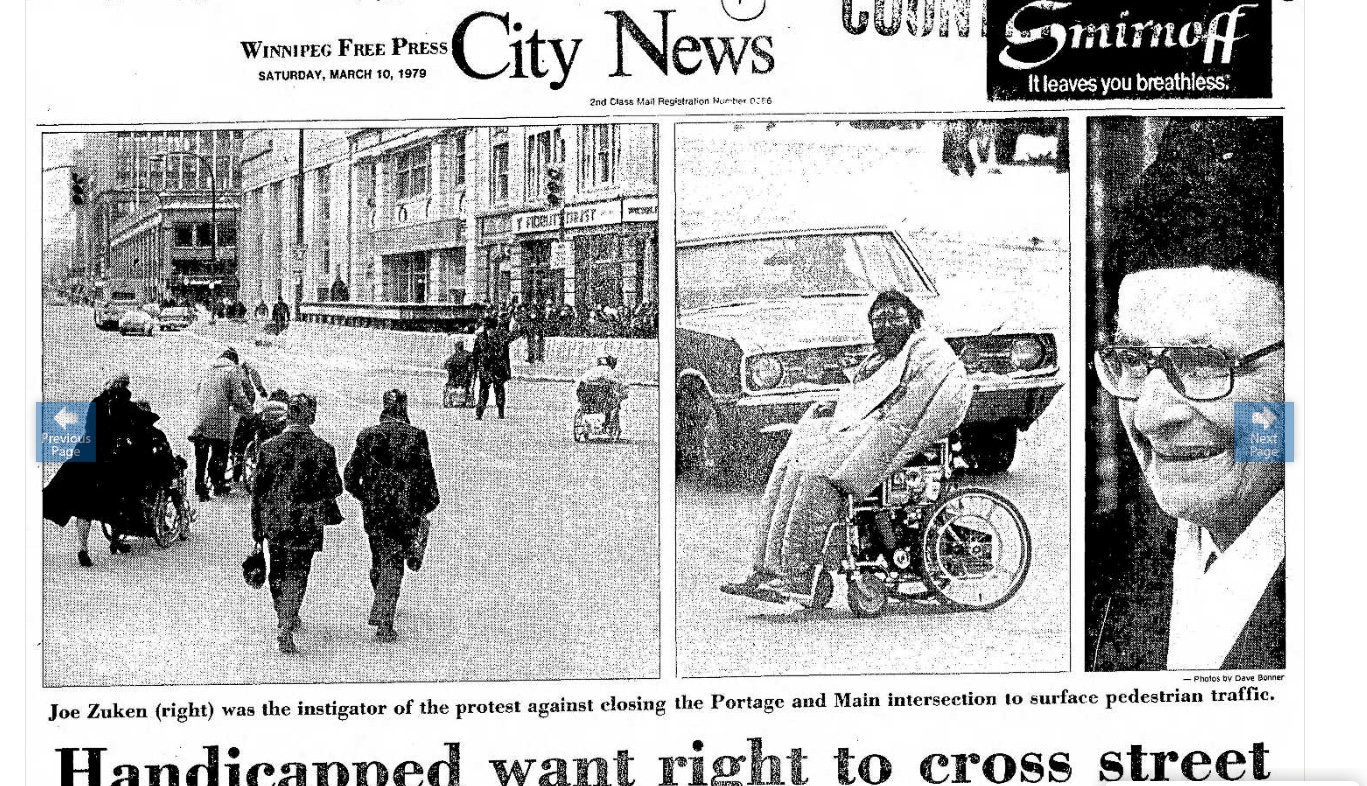

Nearly forty years ago, in March 1979, Winnipeg city councillor Joe Zuken led a band of a dozen or so pedestrians in what is likely to have been city’s most celebrated act of jaywalking. The day before, city council’s ban on pedestrian crossing of Portage and Main had come into effect. Zuken was making good on his promise to defy the ban by leading supporters on a short but windy trek that saw them complete a circuit, walking from each corner to the next.

Photo: Front row, left to right – John Robertson, Joe Zuken, Grant Wichenko, Leonard Marco, Evelyn Shapiro. Behnd Zuken: Jim Maloway. Courtesy of Winnipeg Tribune Photo Collection, University of Manitoba. March , 1979.

Photographs of the day constitute a stern reminder that Portage and Main’s reputation for being a cold and windy place is not undeserved. Most of Zuken’s supporters are wearing bulky parkas and have their heads tucked into fur-lined hoods and toques. Only Zuken, presumably accustomed to the cold by his years of sailing against the political wind, stands out in this regard. Hatless, he determinedly leads his band clad in an overcoat.

No one was arrested, no one was charged for this act of civil disobedience. The attorney general of the day said he did not wish to give the protest any additional publicity.

What Zuken and his supporters were protesting was not simply a ban on surface crossing—although there was plenty to protest about that ban, including the shameful lack of attention that had been paid to the needs of people with disabilities.

The true object of Zuken’s protest was Winnipeg city council’s longstanding inability to resist the siren song of the property developer. The ban on pedestrian crossing was part of a much larger exercise in corporate welfare, in which the city provided extensive support to a multinational development company, despite the fact that the developer continued to constantly change the nature of its proposed development. In the process pedestrians were reconceived as potential consumers. Banned from the public pathway, they were to be funneled through developer-owned underground shopping malls.

The closure of Portage and Main is wrapped up in the history of the building that looms over the southwest corner of the intersection. In 1971 the Trizec Corporation, a high-profile development company that brought together British, U.S., and Canadian money announced that along with the Bank of Nova Scotia, it was interested in developing a bank building, an apartment tower, a hotel, and a shopping mall on the site where the city was planning to construct an underground parking lot.

Zuken opposed the deal from the outset, pointing out that the city would be obliged to assemble the land and build the parking lot and the building foundation without any guarantee that Trizec would, in the end, build anything. By 1975, the City had bought and cleared the land still without receiving any guarantee as to what was to be built. Trizec then threatened to drop out of the project if the city did not agree an underground pedestrian concourse (and pay 80 per cent of the construction costs and 100 per cent of the maintenance costs of concourse) and ban surface crossing of the intersection (to force people into the concourse). By this point, opposition to the project was mounting: the 1976 vote to ban surface crossing passed city council by a single vote.

Two years later Trizec revealed its final plans: gone were the hotel and the second office tower (for which the city had built foundations) and the shopping mall was scaled back. Most of the land that the city accumulated has sat empty for the past forty years: part of it was the bleakest of urban “plazas” imaginable, while the rest of the surface area was covered with the flat roofing of the mall below. It is such a dead no-go zone that it is doubtful many Winnipeggers even noticed it. The development’s failure to find a place in the city’s life—a significant failure for any project of so-called ‘urban re-vitalization’—is that few Winnipeggers could identify the name of the 31-storey high-rise at the heart of the story. Given the project’s controversy it was known informally for many years as the Trizec Building. Its formal name was the Commodity Exchange Tower, since it was the home of the Winnipeg Commodity Exchange. But since 2008 it has simply been known as 360 Main Street.

The pedestrian barriers at Portage and Main are a symbol of a failed corporate development model for the city. Removing them will certainly enliven the downtown by putting more people on the streets and serve as a sign of greater openness. But symbols can be diversions: the real questions facing too many Winnipeggers is not where they can cross the street, but where they will lay their heads. On this score city council still finds the call of the developer more attractive that of community organizations. The city’s decision not to grant tax increment financing to Gas the Station redevelopment in Osborne Village obliged that organization to drop its co-op housing component. IKEA, on the other hand, not surprisingly had no problem getting a tax financing break from the city for its “Seasons of Tuxedo” project.

Doug Smith is the author of Joe Zuken: Citizen and Socialist. (Toronto: James Lorimer and Company. 1990).

Joe Zuken (1912 – 1986) served for 42 years as school trustee and City Counsellor in Winnipeg. CCPA Manitoba is proud to be supported in part by the Joseph Zuken Memorial Fund and hosts the Joseph Zuken Activist Awards.

By Shauna MacKinnon

By Shauna MacKinnon

On Thursday September 20, Winnipeg City Council will vote on a motion to clear the way for True North Square (TNS) to receive an $8 million subsidy through the City’s Tax Increment Financing (TIF) program. Council will be asked to waive TIF rules that would require 10% of the 324 TNS rental and condo units to be developed on Hargrave and Carlton Streets to be “affordable”.

TIF is a financial tool that allocates future increases in property taxes for a designated area to pay for improvements within that area, for a specified period of time. TIFs are used in cities across North America as a revitalization tool, and they often include a requirement that housing development include a percentage of affordable units. In Manitoba, TIFs are allowed through provincial legislation. Winnipeg’s official development plan identifies TIF as a strategy for neighbourhood revitalization, including the facilitation of “safe and affordable housing …”. Aligned with this is the City’s Live Downtown – Rental Development Grant Program By-law referred to in the report to Council. The by-law requires that a minimum of 10 % of housing units subsidized through TIFs must be ‘affordable’, which means that rents would be set at or below median market rents, for a minimum of 5 years.

In addition to affordable rent guidelines, the Live Downtown policy outlines specific geographic criteria for TIF. It currently does not include the proposed site of the TNS development. City Council is being asked to support an expansion of the designated area to ensure that TNS qualifies for TIF. If Council supports the proposal that has been endorsed by Executive Policy Committee (EPC), TNS will sidestep the rules, and qualify for a subsidy to develop high-end condos and rental units on property outside of the TIF zone, with no affordability component.

This sets a dangerous precedent for future development, and it defeats the purpose of a TIF program focused on the city’s ‘vision’ of downtown revitalization that includes affordable housing.

For its part, the provincial government has already agreed to a deal. Its contribution to the residential component of the project will be $8 million over 20 years. If the City proposal passes, it will match that amount, giving $16 million in subsidies for housing that won’t be affordable to many, if not most, Winnipeggers.

While the City and Province clear the way for public subsidies for the creation of high-end housing downtown, mid and low-income families in Winnipeg are struggling more than ever to find safe affordable housing. The number of Winnipeggers in “core housing need” increased from 10 percent in 2010 to 12.1 percent in 2017. And the affordable supply continues to shrink. In the downtown alone, close to 300 units of low-cost rental housing have disappeared with the demolition of social housing on River Ave. and Mayfair Place, and with the sale of the provincially owned 185 Smith St.

Enforcing the affordability clause as a requirement for TIF would not create housing for low-income households –median market rents are far more than many households can afford. For example, the median for a two bedroom is $1100.00 per month. At best, enforcing the affordability clause would ensure a small number of new units would be available to moderate income earners. It may not be much, but if all new downtown developments included affordable units, it would make downtown living more accessible.

The City and Provincial government’s enthusiasm to provide public funds for this high-end housing project raises important questions. What is it about this project that justifies overriding an important element of TIF policy? How does it align with the intentions of the Province’s Community Revitalization Tax Increment Financing Act and Winnipeg’s Live Downtown policy? Why offer TIF at all if the project will proceed without it? How does this use of public finances fit with the more important public policy priority—creating more affordable rental housing?

The provincial government is the primary level of government responsible for addressing the housing needs of low-income households. The Province does not currently have a strategy. If it did, ensuring that provincially subsidized developments like TNS include a reasonable number of affordable units would be a reasonable component.

The City of Winnipeg does not have an affordable housing strategy either. It appears to defer to the non-profit End Homelessness Winnipeg initiative to address the housing needs of the most vulnerable. But End Homelessness Winnipeg has no power, and no financial resources to increase the housing supply.

The case for a comprehensive, well financed, intergovernmental strategy to address the shortage of social and affordable housing in Winnipeg has been made for several years. The use of TIF alone won’t solve the problem – not a in a long shot. But TIF is one small tool that can be used to ensure affordable housing is in the mix. The very least private sector developers can do as good corporate citizens, is to abide by the rules if they wish to access public subsidies.

The extent to which governments should subsidize private development in the downtown is a larger debate. But when it comes to subsidies for housing, the City and the Province need to get their priorities straight. Winnipeggers concerned about inequality need to ask ourselves— who benefits when millions of dollars of public funding is used to subsidize high-end housing in a city where an ever-growing number of individuals and families can’t finding housing that they can afford?

Shauna MacKinnon is Associate Professor in the department of Urban and Inner City Studies, University of Winnipeg, a long-time member of the Right to Housing Coalition and a CCPA Manitoba Research Associate.

By Anne Lindsey

I went to visit a friend and colleague recently – someone I hadn’t seen for awhile. Sandra Madray was in the final stages of cancer. She was dying. I was shocked and deeply saddened to see the physical changes the disease had wrought on my beautiful friend. She was so thin, and in so much pain.

Cancer is horrific in every circumstance but the cruel irony in Sandra’s situation is that she worked much of her adult life in a volunteer capacity to prevent cancer and other illnesses. In particular, those caused by and associated with environmental and industrial chemicals.

As a co-founder (with Margaret Friesen) of the local group, Chemical Sensitivities Manitoba and an advisor to the national organization, Prevent Cancer Now, she participated as a citizen/environmental representative in countless government consultations on laws and regulations regarding chemicals. She sat on the National Stakeholder Advisory Council for the Chemicals Management Plan and on the Canada-United States Regulatory Cooperation Council. She served on the Board of the Manitoba Eco-Network for several years, and was active in the Children’s Health and Environment Partnership.

Sandra educated herself (and others) on the science and public policy of chemical exposure and what it means for human health. Studying reams of documents, she did the arduous and often thankless work that many of us have neither the patience, nor the appetite for, as we trust hopefully that our governments will make the right decisions in the public interest.

Because she did that work, she knew that our hopeful trust is misplaced and that most regulatory decisions about chemicals are not taken with the utmost care to protect health or the environment, but rather, lean heavily toward maximizing commercial profits and expedience. She knew that as a result, we inhabit a chemical soup of hazardous exposures to pesticides, cosmetics, plastics, vehicle and power plant emissions and other by-products of the hydrocarbon society.

Sandra’s cancer may or may not have been attributable to environmental or workplace exposures, but many cancers are, and in all those cases, the pain and suffering, the unmitigated sadness and loss for family and friends is probably preventable.

Always kind, generous and with good humour and deep conviction, Sandra used her knowledge to advocate tirelessly for better solutions to society’s problems. She campaigned especially for the most vulnerable – for children, the elderly, the chemically-sensitive (of which she was one) and the immune-compromised. A quiet warrior, she never sought special recognition for her work.

Some of the efforts she engaged in were successful – one recent example being the Manitoba law to prohibit many chemical pesticides in lawn care. With her own urban yard – an oasis of gorgeous native plants, buzzing and bright with butterflies and pollinators – as an example of better, healthful solutions for green space management, she worked with a coalition of groups to end unnecessary exposures to so-called “cosmetic” pesticides, some of which are linked in epidemiological studies to a variety of diseases, including cancer, respiratory and neurological/developmental problems. When Manitoba joined numerous other provinces in legislating against lawn chemicals, it was a small, but significant step forward in preventive medicine.

It is beyond sad that in Manitoba, it now seems destined to be reversed. Even though recent polling shows that most Manitobans consider pesticide-free to be the best approach, powerful forces support chemical solutions for weed control, and they appear to have the ear of the current government behind the scenes. Possibly acting on inside-knowledge, one lawn company owner was quoted in Home Décor and Renovations Magazine as saying that the (regulation) would be amended for 2019, and that he was optimistic that it would allow “licensed lawn care professionals to resume the use of more effective weed control products.” We can only surmise that he was referring to substances like 2,4-D, dicamba and mecoprop.

As citizens, not only must we make every effort to avoid unnecessary products like cosmetic pesticides and scents, we must also continue to encourage our government not to take this terribly backward step. In fact, it would actually be more appropriate to strengthen the law by adding glyphosate-based compounds, such as Roundup, a weed control product with links to cancer, to the list of prohibited substances. Round-Up’s sordid history of cover ups by its manufacturer, including the fact that its carcinogenic properties were long known about and hidden, is steadily being revealed in court challenges brought by cancer victims.

Sandra will not be with us to see a possible reversal of the policy that she contributed to, and once again, have to endure the impacts of lawn pesticides on her chemically-sensitive body. But if this change of policy comes to pass, so many will be impacted, including the children and all the other vulnerable people that she worked so hard to protect. How many of them will have to sicken and perhaps die before a clean, common sense and precautionary approach to green spaces is adopted once and for all in Manitoba? For Sandra Madray’s sake, let this number be zero.

Sandra passed away at the age of 68, on August 17, 2018, with her beloved husband Winston and family members at her side.

First published in the Winnipeg Free Press September 8, 2018

Anne Lindsey is formerly the Executive Director of the Manitoba Eco-Network, a long-time activist, a member of the group, Cosmetic Pesticide Ban Manitoba and a Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives Manitoba Research Associate.

By Binesi Boulanger

Indigenous peoples have a troubled relationship with the systems that have been imposed by settler colonial populations. The imposition of education through the residential school system was devastating to Indigenous peoples, with the legacy living on in Canada’s child welfare system. Part of ending this cycle of the removal of children means providing culturally relevant and quality child care. Quality, affordable, accessible and culturally relevant publicly-funded child care would provide Indigenous families with additional supports while parents advance their educations and obtain meaningful employment.

An innovative way to support Indigenous people’s language revitalization movement would be through Early Learning and Child Care (ELCC) programs. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) 12th Call to Action directly addresses the need for relevant ELCC programs for Indigenous children. The right to have language-based education programs for Indigenous children is also protected in the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous (UNDRIP) People article 14, section 3. It is important to view ELCC programs as a significant part of a child’s education and integral to their development.

The federal government is responsible for maintaining a working relationship with Indigenous people in Canada. The federal government is required to fund on-reserve projects/initiatives/services as many on-reserve families lack licensed child care. Indigenous children experience a gap in access to culturally relevant Early Childhood Education (ECE) programs off-reserve as well. UNDRIP and the TRC’s 12th Call to Action mandates the expansion of Indigenous ECE programs as a responsibility of the federal, provincial, and territorial governments wherever there is an Indigenous population in need of child care.

Indigenous languages in Canada have been endangered for decades. Residential schools prevented their students from speaking their native language. 25 Indigenous languages in Canada have less than 500 fluent speakers.

It is important to give children the opportunity to learn another language while in ELCC programming. This is especially important for Indigenous children, as many of their families and those in their community had their languages and cultural practices suppressed by the government, and by extension the education system. Incorporating Indigenous language programming within a child care setting and funding the creation of new programs is an act of reconciliation, offering both children and their families the opportunity to heal.

Language gives speakers knowledge about their culture, which helps children to develop a sense of belonging through their cultural identity. Children who learn a second language develop better problem-solving skills and better critical thinking skills. The most important way to keep a language alive is teaching younger generations.

In response to aging populations of language speakers, Indigenous peoples in different parts of the world developed ‘Language Nests’ as their response to the crisis. Language Nests are child care programs where children are exposed to an Indigenous language extensively to create a new generation of fluent speakers to keep the language alive. Language Nests also encourage children’s parents to learn the language and use it at home.

There are Indigenous Language Nests around the world and they have been very effective in helping Indigenous peoples to maintain their language(s). In New Zealand in 1982 they began ‘Te Kohanga Reo’, a child care program geared towards teaching children the Maori language. This program was extremely successful and today there are more than 460 programs in New Zealand. In 1984, Hawaiians began their process of opening up Language Nests, with the first Punana Leo opening up in Kekaha, Kaua’I.This program increased the number of speakers under 18 from about 50 in 1982 to over 10,000 today. In Canada, there are numerous examples of Indigenous communities implementing full immersion language programming. British Columbia, Ontario, and Mohawk communities within Canada have been very active in developing and providing immersive language-based early childhood education.

While there are Indigenous led child care centres and licensed ELCC programs in Manitoba both on and off-reserve, there are no fully funded language specific programs modeled like the Language Nests being run as an option for parents seeking child care.

Encouraging the federal government to begin offering education incentives to support Indigenous people to work in early childhood education would be a step in the right direction. Offering language-based programs at colleges and universities for free in order to further equip the Indigenous population with the tools they need to run language-based culturally relevant Early Learning and Child Care (ELCC) programs would be an act of reconciliation. Providing adequate funding for communities both on and off-reserve to manage Indigenous language-based ELCC programming is important as well. These steps, along with increasing the number of publicly-funded child care spaces to meet the significant demand for child care, would help revitalize Indigenous languages and be a meaningful step towards reconciliation.

Binesi Boulanger is a law student at the University of Manitoba and was the summer Childcare Research and Engagement Coordinator at the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives Manitoba and the Child Care Coalition of Manitoba.

A fully referenced version is available upon request to ccpamb@policyalternatives.ca

Follow us!