By Paul Moist

Pursuant to new provincial and federal effluent guidelines, the City of Portage la Prairie is required to upgrade its wastewater facilities, known as the Water Pollution Control Facility (WPCF). The new Public-Private Partnership (P3) project has not undergone public scrutiny. Past examples point to P3s being more expensive than public management of these project.

First published on CBC online edition Dec 3, 2016

By Ellen Smirl

Increasing tragic deaths from Fentanyl are raising calls to deal with this crisis. Evidence shows that controlling supply and criminalizing drug users does not address the root causes of addictions, which are complex and multi-faceted. Research shows that supports to those experiencing addictions, both harm reduction and treatment, are needed as this piece will discuss.

The first in a series

Compiled by Micah Zerbe, CCPA MB Research Affiliate

Population indicators

1,303,900 Manitoba’s population estimated by Statistics Canada as of January 1, 2016.[1]

16,200 The amount the Manitoba Bureau of Statistics estimates Statistics Canada undercounted Manitoba’s population number above. This impacts per capita transfers from the federal government to Manitoba.

1.71% Manitoba’s population growth rate from July 1, 2015 to July 1, 2016. Canada’s growth rate for the same period was 1.22%.[2]

1.6% Manitoba’s population growth rate for people aged 20-34 from 2014 to 2015.[3]

37.8 Manitoba’s median age in 2011. Canada’s median age was 40.0.[4]

First Nations & Indigenous people

21.0 Median age for First Nations people in Manitoba in 2011. This is due to higher fertility rates and lower life expectancy as a result of the impact of colonization and systematic oppression.[5]

17% Percentage of Manitoba’s population represented by Aboriginal peoples in 2011. Aboriginal peoples represented 5.6% of Canada’s total population.[6]

2.67% Expected 2016 population growth rate for First Nations peoples in Manitoba.[7]

Migration

10,400 Net migration to Manitoba in 2015, including international migration and interprovincial migration.[8]

6,971 Manitoba’s net interprovincial migration population loss in 2015. The loss in 2014 was 7,336. 2015 was the first year that the interprovincial migration loss had decreased since 2009.[9]

37.7% Percentage of Manitobans who left to other provinces in 2015 who were aged 20-34. This is the second lowest of all the provinces after Alberta at 35.3%. For Saskatchewan this percentage is 39.0% and for the Maritimes it is 43.7%.[10]

81% Percentage of interprovincial migrants who left Manitoba and went to Alberta, Ontario, or British Columbia in 2015.[11]

Immigration

6.2% Percentage of Canada’s total immigrants that were received by Manitoba in 2014. Manitoba’s population represented only 3.6% of Canada’s total population.[12]

13,300 Number of international migrants to Manitoba in 2015. This follows Manitoba’s record-breaking 14,600 migrants in 2014.

12,849 Number of immigrants in 2014 who came in the economic class (79.2%).[13]

1,831 Number of immigrants in 2014 who came in the family class (11.3%).[14]

1,495 Number of immigrants in 2014 who came in the refugee class (9.2%).[15]

85.1% Percentage of Manitoba immigrants in 2014 for whom Winnipeg was the final destination.[16]

1,100 Number of Syrian refugees that Manitoba welcomed between November 4, 2015 and August 7, 2016.[17]

22% Percentage of Canada’s privately sponsored refugees that settled in Manitoba. Manitoba also settled almost 6% of all government sponsored refugees.[18]

References

[1] Manitoba Bureau of Statistics, The Review 2015. [Winnipeg]. June 21, 2016.

[2] Statistics Canada. Table 051-0005 – Estimates of population, Canada, provinces and territories, quarterly (persons), CANSIM (database). (accessed: Oct 4, 2016)

[3] Statistics Canada, Table 051-0001 – Estimates of population, by age group and sex for July 1, Canada, provinces and territories, annual (persons unless otherwise noted), CANSIM (database). (accessed: September 19, 2016)

[4] Statistics Canada, Table 051-0001 – Estimates of population, by age group and sex for July 1, Canada, provinces and territories, annual (persons unless otherwise noted), CANSIM (database). (accessed: September 19, 2016)

[5] Statistics Canada. 2013. Manitoba (Code 46) (table). National Household Survey (NHS) Profile. 2011 National Household Survey. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 99-004-XWE. Ottawa. Released September 11, 2013. (accessed September 14, 2016).

[6] Statistics Canada. 2013. Manitoba (Code 46) (table). National Household Survey (NHS) Profile. 2011 National Household Survey. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 99-004-XWE. Ottawa. Released September 11, 2013. (accessed September 14, 2016).

[7] Manitoba Bureau of Statistics, Statistics Canada’s First Nations and Métis population projections – Manitoba highlights, [Winnipeg], 2016. http://www.gov.mb.ca/mbs/reports/pubs/demographic_impacts_2015/ mbs_demo_impact_2015_a2_statcan_aboriginal_projection.pdf

[8] Manitoba Bureau of Statistics, Latest Population Estimates: April 2016, [Winnipeg], 2016. http://www.gov.mb.ca/ mbs/pubs/de_popn-qrt-latest.pdf

[9] Manitoba Bureau of Statistics, Latest Population Estimates: April 2016, [Winnipeg], 2016. http://www.gov.mb.ca/ mbs/pubs/de_popn-qrt-latest.pdf

[10] Statistics Canada, Table 051-0012 – Interprovincial migrants, by age group and sex, Canada, provinces and territories, annual (persons), CANSIM (database). (accessed: September 14, 2016).

[11] Statistics Canada, Table 051-0019 – Interprovincial migrants, by province or territory of origin and destination, annual (persons), CANSIM (database). (accessed: September 14, 2016)

[12] Manitoba Labour and Immigration, Manitoba Immigration Facts 2014 Statistical Report, [Winnipeg], 2015. http://www.gov.mb.ca/labour/immigration/pdf/mb_imm_facts_rep_2014.pdf

[13] Manitoba Labour and Immigration, Manitoba Immigration Facts 2014 Statistical Report, [Winnipeg], 2015. http://www.gov.mb.ca/labour/immigration/pdf/mb_imm_facts_rep_2014.pdf

[14] Manitoba Labour and Immigration, Manitoba Immigration Facts 2014 Statistical Report, [Winnipeg], 2015. http://www.gov.mb.ca/labour/immigration/pdf/mb_imm_facts_rep_2014.pdf

[15] Manitoba Labour and Immigration, Manitoba Immigration Facts 2014 Statistical Report, [Winnipeg], 2015. http://www.gov.mb.ca/labour/immigration/pdf/mb_imm_facts_rep_2014.pdf

[16] Manitoba Labour and Immigration, Manitoba Immigration Facts 2014 Statistical Report, [Winnipeg], 2015. http://www.gov.mb.ca/labour/immigration/pdf/mb_imm_facts_rep_2014.pdf

[17] Citizenship and Immigration Canada, Map of destination communities and service provider organizations, August 25, 2016. Accessed September 16, 2016. http://www.cic.gc.ca/english/refugees/welcome/map.asp

[18] Manitoba Labour and Immigration, Manitoba Immigration Facts 2014 Statistical Report, [Winnipeg], 2015. http://www.gov.mb.ca/labour/immigration/pdf/mb_imm_facts_rep_2014.pdf

By Shauna MacKinnon

“ the social and economic conditions that render children vulnerable to abuse and neglect are well beyond the scope of the child welfare system” (Hon. Ted Hughes, Commissioner, The Legacy of Phoenix Sinclair: Achieving the Best for All Our Children).

Phoenix Sinclair spent much of her young life in and out of the care of Child and Family Services. She died at the hands of her parents in 2005.

On December 31, 2013, the Phoenix Sinclair Inquiry Commission released its much anticipated final report. Also known as the “Hughes Report” this comprehensive, 3-volume, 870-page document examines the circumstances surrounding the tragic death of 5-year old Phoenix Sinclair and outlines 62 recommendations for action resulting from 21 months of intense proceedings.

If the new provincial government had shown a certain amount of restraint up until now, it seemed much more willing to show its hand in Monday’s Throne Speech. A few strong messages emerged: public-sector workers are in for a rough ride; there’s going to be a strong push towards privatization on several levels; and there’s nothing concrete for Manitoba’s northern communities.

It all adds up to a strong austerity agenda.

Before any details were revealed, a false picture of the province’s financial situation was drawn. It was painted with broad strokes to be sure, splattered with words like “fix” and “repair”.

While it is widely recognized that Aboriginal people are over-represented in the urban homeless population, most research has focused on Aboriginal homelessness in metropolitan areas. Very little attention has been paid to the issue in small northern towns. The small amount of research that has been done on the topic suggests that there are also challenges associated with Aboriginal homelessness in more remote urban areas, and that there are unique aspects to homeless populations in these areas. This study attempts to contribute to our knowledge about urban Aboriginal homelessness with research on this issues in Flin Flon, Manitoba, a small northern mining community.

Read full report

IRCOM staff and participants.

By Jill Bucklaschuk

As housing advocates across the country recognize National Housing Day on November 22nd, we must continue to acknowledge the central role of housing in building inclusive communities and seek ways to ensure that all low-income families have access to affordable, safe, and good quality housing. Vulnerable and marginalized populations such as newly arrived immigrant and refugee families all too often suffer the indignity of scouring the private rental market for suitable housing only to face discrimination, unaffordable rental rates, poorly cared for buildings, and undesirable neighbourhoods. Upon arrival in Canada, obtaining housing is a top priority for newcomer families, but finding a suitable residence proves to be a profound challenge without social networks, employment prospects, and knowledge about the nature of both rental markets and neighbourhoods.

By Josh Brandon

By Josh Brandon

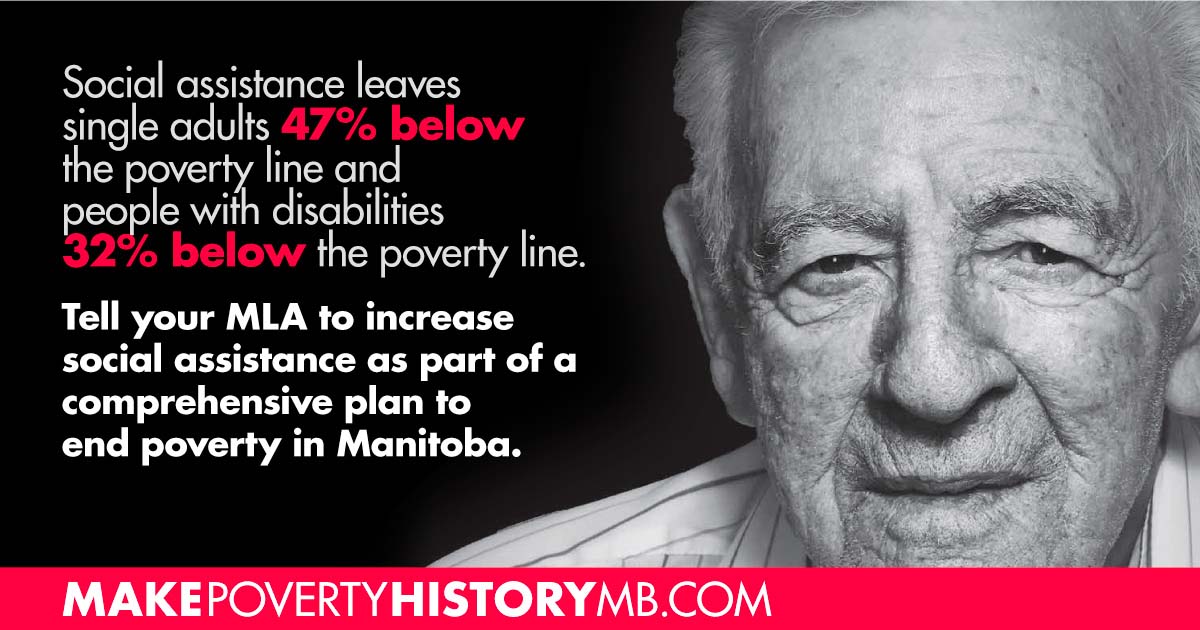

When Lieutenant Governor Janice Filmon delivers the throne speech November 21, a plan for poverty reduction should top the government’s priority list. The Province has promised a plan by next year’s budget and Manitobans are waiting for details.

Poverty comes in many forms, most of them hidden from public view: an empty fridge at the end of the month; a coolness in the room, because hydro rates have gone up and income hasn’t; a mom juggling between her threadbare budget and her child’s unpredictable growth spurts. Poverty reflects the impossible choice of asking not what can be done without, but what is essential that will nonetheless be sacrificed.

Basic Personal Exemption (BPE) increases are being brought in by the new provincial government under the auspices of reducing poverty. The BPE is the floor at which we start paying provincial income taxes.

Not only will these changes do little to help low-income earners, they will bring in less revenue to the provincial purse and undermine the public services that all Manitobans need, especially the poor. Addressing poverty requires more revenue directed at reducing poverty, not less. This is why reducing tax revenue through the BPE in the name of poverty is particularly insidious.

Follow us!